Rediscovering the Pioneering Cinema of Mihajlo Al. Popović: With Faith in God (1932)

By Mina Radović

The Yugoslav silent cinema is one of the most beautiful chapters in film history. To be opened one has to understand its historical context. The wealth of domestic silent film solely available in the Yugoslav Cinematheque in Belgrade and across the archives of the former Yugoslavia has meant that scholars, archivists, curators, and cinephiles have had to go to the archive to watch the films while many key films were only rediscovered and restored in the last decades, from the 1980s with the unearthing of the work of Serbian pioneer Đorđe Bogdanović, the first domestic film producer and the person whose recordings of the Balkan Wars and the First World War are singular historical documents, and the early 2000s with Čiča Ilija Stanojević’s Karađorđe (1911), one of the world’s first feature films and the first one from Serbia and the Balkan peninsula. For the significance of this chapter to be appreciated, one has to understand the mode of production, cinematographic tradition, and film culture that emerged in the silent period of Yugoslav cinema. While many national cinemas since ‘Lumiere’s miracle’ went down the route of nationalization and the creation of a production and by the 1910s studio-based infrastructure, as was the case with France, Italy, Denmark, Britain, and the United States, film culture and production in Serbia and the South Slavic territories that would by 1918 constitute the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes developed from the grass roots. Independent film producers, self-organized enthusiasts, cinema owners, and cinephiles who were well-established figures in other fields, including photography, theatre, literature but also trade, finance, sport, military, and civil services, turned to film and this practice only grew and diversified in the new and united monarchy (Kosanović, 2011).

As our own Aromanian discoverers of film the Manaki Brothers settled in Yugoslavia and pioneer Ernest Bošnjak set up his first studio, new directors emerged. Kosta Novaković, Josip Novak, Miodrag Djordjević, Stevan Mišković, Žarko Djordjević, Andrija and Zarija Djokić quickly established their reputations as the most formidable film artists in Yugoslavia. Cineastes gathered around the ‘Klub filmofila’ (‘Filmophile Club’ where pioneers such as Novak learned about filmmaking for the first time) and between the mid-1920s and early 1930s three major film schools opened in Belgrade, including Aleksandar Čerepov’s ‘Filmska škola’ at the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (Jovičić, 2019). Aesthetic expression flourished and film culture blossomed, from the film clubs to the King’s court. The state supported the production of educational and documentary films and by 1932 created a much greater incentive to support the country’s cinema. The law regulating film distribution which required at least 15% domestic productions on cinema repertoires led to immense increase in domestic production, with as many as 326 films being produced in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1932, a total which counts more than all the productions produced in the Balkans up to that point (Jovičić, 2019).

This was the same year when the quiet pioneer, who until then worked as a cinematographer and only recently set up his own production studio MAP Film, made his first feature film. Born in Belgrade, a graduate of commerce and trade, the young man turned to film with a great love. He began shooting documentaries, directed the camera of Ranko Jovanović and Milutin Ignjačević’s Kroz buru i oganj/Through Storm and Fire and in 1930 was one of the founders of the Yugoslav Film Club (Jovičić, 2019; Erdeljanović, 2020). Mihajlo Al. Popović (1908-1990) directed Sa Verom u Boga/With Faith in God in 1932 and single handedly made the leap from theatrical narrative to film language, from ‘the cinema of attractions’ to the cinema of poetry.

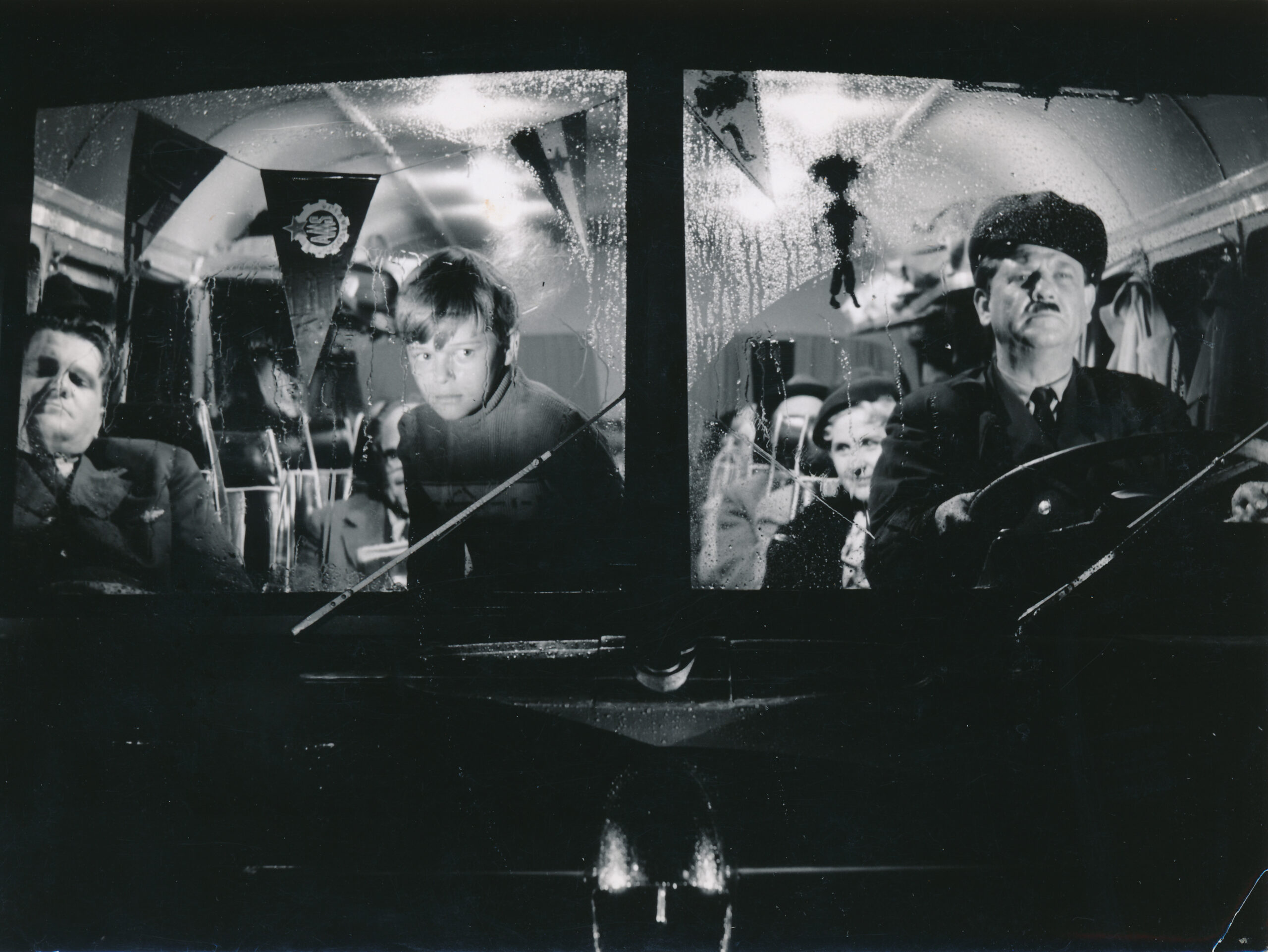

With Faith in God follows the suffering of a family in rural Serbia during World War I. The film depicts the everyday life of the villagers, their reverent family life, the adults’ working with animals and land, the play of children, and the romance that imbues younger couples. All this is cut short with the Sarajevo Assassination, the news of which reaches the village. Soon after, as war breaks out, the men go to the front. As sickness descends upon the household, the film shows the unique perspective of the mothers and children who stayed behind the frontline. There are several things that make With Faith in God a fascinating work of cinema.

First, the film has a refined sense for detail and drawing out the invisible connections that make everyday life beautiful. The film opens on a dark bedroom as a young woman braids her hair and the first light of day overshadows a part of the room. A quiet shot of the sun follows. The film magnifies our sense for meaning, as we serdeee the maiden walking out, in front of a mirror happily fixing the garment that covers her hair, talking a drink of water (at this point the intertitles tell us that ‘everyone has a delight of their own’), pouring the water down, then we see a flower bed at her feet with bustling insects. Then a close-up shot of a bee house, an elderly beekeeper turning his board full of bees and honey, a mother feeding a group of baby rabbits out of her hand, piglets feeding from mother pig, and an intertitle which introduces us to ‘the head of the family’, the man taking out his horse and then his son at work. This is a seemingly naturalistic and simple opening, but it visually conveys the poetry of everyday life. There are no great elements. Rather, the film focuses our attention on the small and unnoticeable details that make everyday life beautiful – the sun peering in, the drink of water, the flowers, the bees – but it also reveals the unspoken connections that bring joy in everyday life – breathing in a new day, the girl’s feet resting on the living flower bed, the bees with their beekeeper, the human mother and baby rabbits, the piglets and mother pig, the father and son. We not only read about delight, but we sense it, as the film unveils the vibrant organic connections that exist between the members of a family, the animals with which they live and the nature to which they tend. This attention to detail and invisible connections imbues the fabric of the whole film.

The depiction of the war through its absence is another aspect which makes the film unique. Much of the film’s ‘action’ is to be found in the village and even when we transition to the frontline the war is framed not through the battle but through the perspective of the families who stayed behind. Shots of working women, children with mothers, or elderly matriarch looking on from homestead in contrast to men at march makes the village our resting point. The most powerful scene of the film serves as another good example: the matriarch sick in bed, surrounded by family, sees her son as a soldier in the battlefield looking back at her, he is surrounded by fire and the shot is juxtaposed with Christ on the Cross shrouded by fire and smoke. While there is an initial expression of grief in the mother’s eyes her vision of Christ (sheltering her son and symbolically her family) brings her peace and she reposes. These examples serve also to show the third way in which the film stands out, namely through the lyrical negotiation of on-screen and off-screen space the film conveys the unspoken connections between mother and son, peace and suffering, life and death, historical and eternal, man and God, bridged by the True Person on the Cross.

To understand the poetic depth of the film it is worth comparing it with Carl Theodor Dreyer’s contemporaneous The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). While in the face of death Dreyer emphasizes pain, Popović brings out peace, while Dreyer shows the immediacy of external suffering, Popović shows the quiet nature of long-suffering, and most importantly, while Dreyer heightens the visual drama to make you feel ever drop of Joan’s tears, Popović brings out the internal joys which represent a people’s response to their crucifixion, well embodied in the image of Christ on the cross shrouded in the fires of the First World War, but also going further, to show the peace that follows crucifixion as Christ ‘takes the soul’ of the matriarch. The film ends with the father and son reunited. However, this reunion is not framed as melodramatic victory but as a quiet, personal one in which the meaning of resurrection is to be found: the gift of new life which follows immeasurable, involuntary suffering.

Mihajlo Al. Popović continued to produce, shoot, and direct films throughout the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, mostly working on documentaries but he never made another feature film. After the Second World War, he worked as a cinematographer and the visionary behind the works of Žika Mitrović, Stole Janković, and Mladomir Puriša Đorđević. While largely unknown and, because of the subject of faith, presumably unpopular with the socialist regime, his work was rediscovered by the Yugoslav Cinematheque in the 1980s. Now hailed as the greatest Yugoslav silent film, With Faith in God was restored by Stevan Jovičić and his colleagues in the film archive and screened at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in 1988 to a standing ovation.

At the time he made the film Mihajlo Al. Popović was 24 years old and as such has a good shot for creating the best debut in film history – closely followed by Jan Němec, Orson Welles, and Samira Makhmalbaf. More importantly, however, by delicately expressing the trials brought upon the innocent and bringing out the endurance that only faith can provide Mihajlo Al. Popović’s With Faith in God represents one of the earliest and to this day most dynamic representations of spiritual life on film. His highly conscientious, ascetic, and altogether sensitive approach to film language in treating matters of faith has its only heir in the work of Andrei Tarkovsky. With Faith in God is poetry at its best.

References

Erdeljanović, Aleksandar. “Sa verom u Boga” in Jugoslovenska Kinoteka, Belgrade, 9. April 2020; Last Accessed: 16. September 2021. http://www.kinoteka.org.rs/film-sa-verom-u-boga-na-youtube-kanalu-kinoteke/

Jovičić, Stevan. “The Cinema in Serbia 1896-1941” in Studies in Eastern European Cinema (foreword and translation by Mina Radović), Vol. 10, Issue 3, Abingdon/New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2019.

Kosanović, Dejan. Kinematografija i Film u Kraljevini SHS/Kraljevini Jugoslaviji 1918-1941. Belgrade, Film Center Serbia, 2011.

Author Biography: Mina Radović is the founder, director, and head of programming of Liberating Cinema. A FIAF-trained archivist, curator, critic, doctoral researcher, and pedagogue in film at Goldsmiths, University of London, he is an expert in Serbian and Yugoslav cinema.

This original essay was written for An Introduction to Yugoslav Cinema, Liberating Cinema Film Series 2021.