A Single Spark and South Korea’s Transition into Democracy

By Connor McMorran

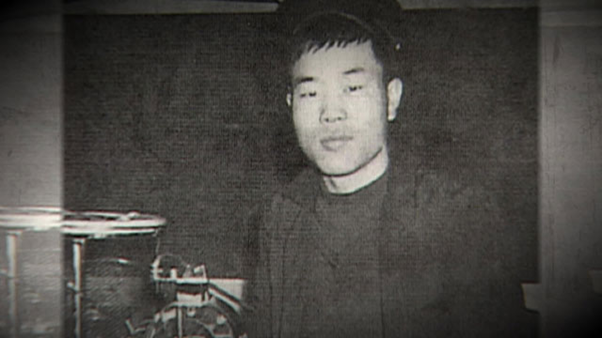

On 13th November 1970, a young textile worker named Jeon Tae-il protested harsh working conditions by self-immolating and running through the streets shouting, “Obey the Labour Standards Act!”. Though Jeon’s solitary act was not the first protest concerning labour standards in South Korea, it nevertheless has retrospectively become, as Bruce Cummings states, “the touchstone of the labour movement”.[1] While Jeon’s sacrifice brought attention to the various oppressive and exploitative elements inherent in industrial work, leading to his lasting significance as a symbol of resistance for labour rights,[2] his act did little to halt the many abuses suffered by workers during this period. In fact, Cummings highlights Jeon’s act as one of two key reasons[3] behind the implementation of dictator Park Chung-hee’s Yushin [4] regime in 1972. This decree saw Park not only consolidate his power, removing any term limits on his governance, but also saw a harsher response to protests and strikes under the guise of ‘unity’. Fuelled by an explicitly anti-communist agenda, such labour movements were positioned as directly oppositional to Park’s façade of progress, which required an unquestioning conformity to the principles of Park’s dictate. As part of this new mandate, the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) became more active in its labelling of dissidents as communists, as seen in the case of Reverend Cho Hwa-sun, who was a ‘key catalyst in forming the women’s union’ at Dongil Textile Company, and who was subsequently arrested for being a ‘hidden communist’ in 1972.[5] Under Park Chung-hee, unionism became seen as fundamentally anti-patriotic.

Following Park Chung-hee’s assassination in October 1979 by Kim Chae-gyu,[6] Major General Chun Du-hwan would initiate a coup and begin to take control of the country in December that same year. Despite initial signs of political freedom during this transitional period, it wouldn’t take long for Chun’s iron fist approach to manifest itself against any signs of resistance. Chun soon installed himself as the director of the KCIA, and in May 1980 he initiated a series of highly restrictive measures, implementing martial law and imprisoning many political leaders, academics, and other suspected dissidents. His actions would invoke the Gwangju uprising, wherein thousands of protestors occupied the streets of Gwangju and were met with violent force by the national army, resulting in a massacre of the protestors. Chun, having suppressed the protest with military power, maintained martial law, and continued to further oppress any aspects of South Korean society which threatened his absolute leadership. Among countless other injustices against political opponents and the sustained oppression of the people, in 1981 Chun dissolved the Cheongye Garment Workers’ Union, which was founded following Jeon Tae-il’s act of resistance.

Despite all his attempts at maintaining power and instilling fear among the populace, including the allowance of prolonged detainment and torture under the national security law, Chun found himself ousted by overwhelming protests in June of 1987 in response to both the death by torture of student activist Park Jong-cheol, and Chun’s attempts to situate a puppet leader in power without any electoral process. Though Chun’s chosen successor, long-time collaborator Roh Tae-woo, would ultimately be elected by the people, it was done following the government’s acquiescence to the people and a commitment to amend the constitution and transformation into a democratic society. As the country transitioned from two decades and two successive dictatorships into a capitalist democratic state, its repressive attitude towards unions and labour movements gradually lessened. At the same time, South Korea also enjoyed an open environment in which to discuss history and politics. It was in this very period of transition that South Korean filmmakers began to interrogate and examine the country’s collective traumas of oppression and rampant ideology.

Cinema as Diversion, Cinema as Resistance

Film had been used as a means of diverting the peoples’ attention away from wider social issues as part of Chun’s 3S policy – Sport, Sex, and Screen – which resulted in the South Korean film industry producing many genre films, particularly erotic and horror films.[7] It’s important to acknowledge that South Korean cinema experienced trends of popular genres prior to the 1980s, most notably the martial arts films in the 1970s which emerged as a result of production relationships with Hong Kong, so these waves of genre cinema were not a new experience for the industry. Equally important to note is that that this specific period of a ‘liberated’ approach to on-screen representations of sex was not reflective of a more liberated society, but on the contrary was a means of satiating the populace with the impression of relaxed attitudes to censorship. The implementation of late-night theatre screenings allowed for the success of Madame Aema (애마부인, 1982), wherein a woman engages in multiple affairs while her husband is imprisoned,[8] which in turn not only heralded a wave of erotic productions but also created a lasting franchise of its own sequels.[9] Though Chun’s attempts to deflect public interest away from the Gwangju massacre and his increasing authoritarian rule by using the implication of a liberated cinema experience were ultimately unsuccessful, that it was attempted in the first place helps evidence film’s foregrounded position as a cultural apparatus that could be used to influence a broad range of the populace.

Around the same time as the success of Madame Aema and other genre films, there were numerous student collectives who also hoped to employ film in order to highlight the plight of rural and working-class people. Not content with merely engaging with, and responding to, film on a theoretical level, these various university cinema groups also ‘pioneered alternative cinema in the 1980s’.[10] This was especially the case when several of the groups merged to form the Seoul Film Collective in 1982. The Seoul Film Collective not only published theoretical texts, but also produced films such as the short documentary Surise (수리세, 1984), which featured interviews with farmers as they discussed their lives. By focusing on subjects that were often ignored or otherwise portrayed unfairly in mainstream cinema, these student-led initiatives attempted to use film as a cultural apparatus in support of social justice. In doing so, they imbued the growing independent and alternative cinema culture in South Korea with an ideological drive to highlight the oppressed and raise awareness of the daily struggle and continuous repression of the lower classes in society. The use of newer technologies, such as video, also allowed independent filmmakers to more easily produce films outside of the mainstream system. One key example of such a production is the half-hour long video documentary, Sangyedong Olympics (상계동 올림픽, 1988) which depicted the forced and violent eviction of residents of a lower-class area of Seoul to beautify the area for visiting tourists, athletes, and delegates during the 1988 Seoul Olympic games.

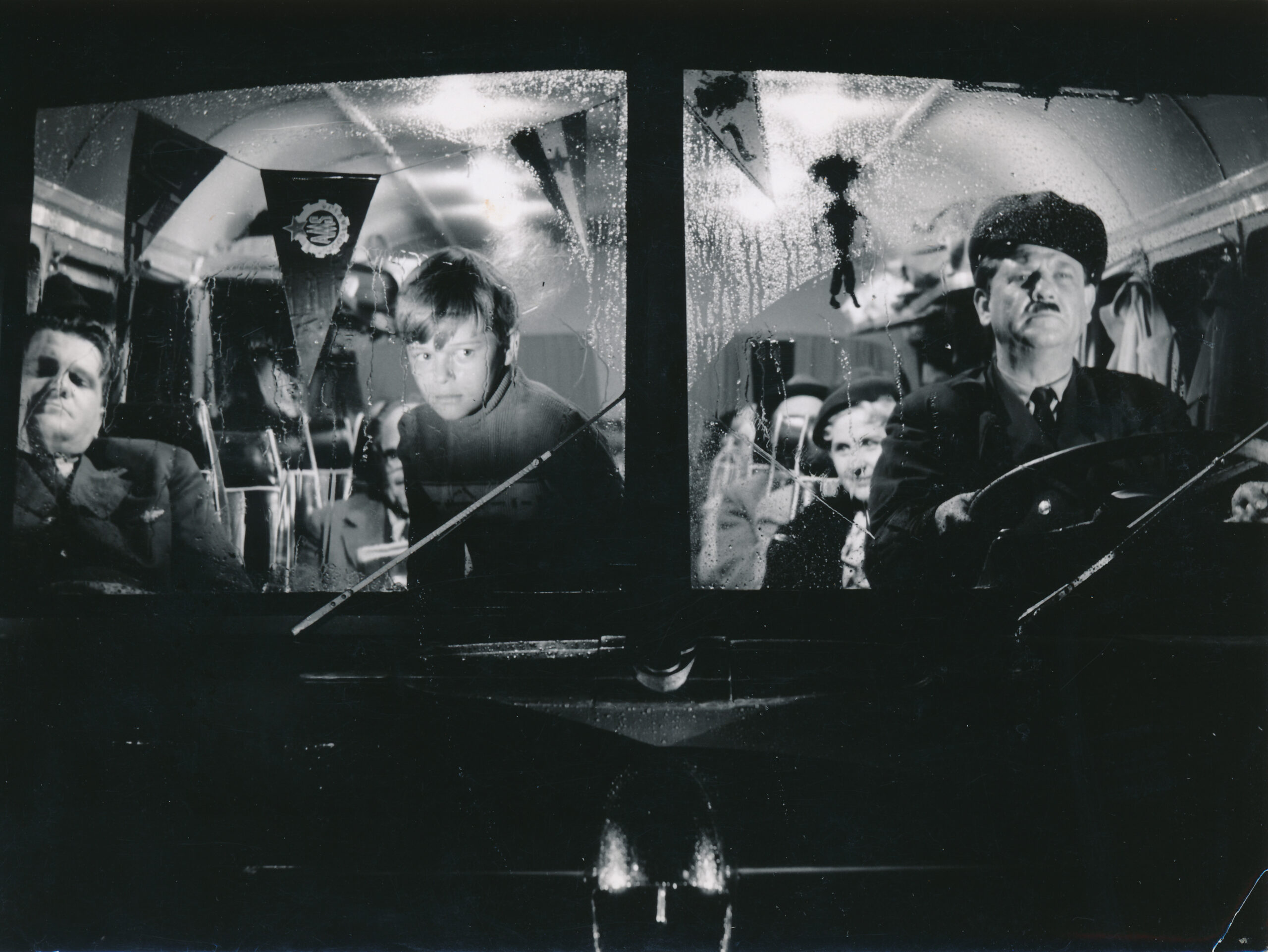

Though these various collectives never managed to achieve a significant breakthrough into the wider cultural consciousness and were thus largely left to organise their own screening spaces and means of providing education, their legacy was maintained by the relatively more successful group Jangsangotmae (장산곷매), who would produce the first feature length independent production, Oh! Dreamland (오 꿈의 나라, 1989), a film which explored the Gwangju massacre through the lens of students. Beginning with the assault of a long-haired student on a bus by a soldier, and ending with a slow zoom onto an American flag accompanied by a military brass performance of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’, the film resolves its collective trauma against a series of cultural oppressors, not just that of Chun’s authoritarian rule, embodying the thriving anti-American spirit that grew in South Korea throughout the 1980s. Jangsangotmae’s follow up film, The Night Before the Strike (파엎전야, 1990) depicted the attempts to unionise by the impoverished and exploited workers at a metalworks factory, and concludes in a powerful montage that links documentary footage of various protests and battles against the police with the image of the metalworker standing proud, his wrench raised in solidarity with the striking workers. Though just as effective as many of the great Soviet productions throughout the twentieth century, the political bluntness of these independent productions perhaps speaks to the significant lack of such socio-politically motivated cinema within South Korea during this period. The independent modes of production and distribution[11] were essential tools to work against the continuing use of cinema as a means of entertainment, and with it distraction, first and foremost among the mainstream industry.

Out of this dichotomy of cinematic employment, and bolstered by the country’s transition into democracy, a selection of disparate filmmakers who responded to this new freedom of expression are often collected under the category of ‘New Korean Cinema’.[12] Though mainstream South Korean cinema had seen a slight movement towards a more socially conscious engagement with the realities of people’s lives, in films like People in the Slum (꼬방동네 사람들, 1982) and Ticket (티켓, 1986), there remained a specific lack of more overt, politically focused mainstream cinema which sought to examine the various contradictions and issues of contemporary society. Somewhat freed from the restrictions of the past, 1988 saw the release of two films which managed to achieve such societal examination, Director Park Kwang-su, who would go on to direct A Single Spark (아름다운 청년 전태일, 1995) had been an active member of the significant Seoul cinema group Yalashung, and his debut feature Chilsu and Mansu (칠수와 만수, 1988) laid the foundations for a career of incisive, socially conscious films which sought to foreground the various struggles of everyday people throughout different periods of history. Chilsu and Mansu follows its eponymous characters, two billboard painters, as they attempt to grapple with their respective lack of social mobility. The two ultimately decide to strike, refusing to be removed from their billboard situated high above the city, initiating a public standoff against the society which denies them their dreams of aspiration and success. The film emphasises class consciousness, primarily by resolving the tensions between the two characters – Chilsu is unable to hold down a job due to his lackadaisical attitude, whereas Mansu is actively denied jobs because of his father’s unrepentant communism – in a show, and celebration of, solidarity against the oppressive structures within South Korea’s emerging society.

A far cry from Chilsu and Mansu’s penetrating, microcosmic drama, yet just as politically motivated, was Jang Seon-wu’s caustic satire The Age of Success (성공시대, 1988). Depicting the war between two artificial sweetener companies, the film focuses on the attempts by Kim Pan-chok,[13] a seller who believes completely in the meritocratic façade suggested by corporation culture. Pan-chok’s personality is evidenced in the opening shots of his apartment. Everything is in order, and the film lingers on a picture of Hitler and other high-ranking Nazis walking under the Eiffel Tower which adorns one of the walls. This link between capitalist desire and fascism is further foregrounded in Pan-chok’s ritual of Sieg Heiling a bank note before leaving his apartment. Despite his initial success, Pan-chok is eventually swindled by his inside source from the rival company, and his failure causes him to be relocated to a dilapidated rural store as punishment. There, however, Pan-chok finds a newfound enthusiasm not for nature, but for the marketable idea of nature, and rushes back to headquarters to pitch his latest idea. Despite his best attempts, his idea is rejected, and Pan-chok dies in a car accident after being forcibly evicted from the department building. The Age of Success is an incensed attack at both the oncoming unfettered capitalism into which South Korea was entering, and also those who wished to participate in its emphasis on profit, marketing, and the ideal of perpetual success.

Despite their differences, both Chilsu and Mansu and The Age of Success explored the overwhelming oppressive nature of the alienated urban city, which was trending further towards corporate visibility and the sublimation of space, time, and movement into production. In doing so, they provided a significant step forward with regard to a more politically focused and socially engaged mainstream cinema in South Korea, a cinema that was eager to attack and question the foundational ideas of progress and liberation that the public was experiencing at the time. As South Korea furthered its transformation into the Western model of a liberal, capitalist, democratic state, filmmakers began to apply this politically motivated approach to examine more specific periods of historic trauma that had until then been forbidden from being discussed. At the same time the wider South Korean economy began to view film as something worthy of significant investment, and the majority of mainstream cinema found itself once again being positioned as primarily a form of entertainment.

History and Trauma

The shift to a historical focus[14] during the early to mid-1990s signals an attempt by South Korean filmmakers to challenge long-held ideological elements of South Korean society. In the Korean War epic North Korean Partisan in South Korea (남부군, 1990), which is based on the writings of the partisan journalist Lee Tae, the struggles and plights of the communist soldiers in their fight against the South are explored in great detail, depicting the shifting relationships and battles experienced by numerous members of the Korean People’s Army. The film presents their struggle for survival as an unrelenting slog, hidden among the mountains and constantly bombarded by superior firepower and aerial attacks, with the South Korean army largely relegated to a faceless entity which only seeks to destroy its enemy. By centring the Northern soldiers, and depicting them in a nuanced and respectful manner, director Jeong Ji-young provides a staunch rebuttal to the decades of increasingly oppositional anti-communist rhetoric that had plagued South Korea under its successive dictatorships. One significant departure from the film’s focus on the Northern army is a scene which also highlights the antagonistic approach to ideology that is found in films of this period. In the middle of a battle, both the North and South call for a cease-fire in order to allow a young child to retrieve their dog from the battle. As the child does so, both sides call out to the child, offering them salvation from the other side. Caught in the middle, the child eventually rejects both and returns to their house, situated in between the two battalions. Despite a moment of acknowledgement between North and South, it doesn’t take long for the insults and agitations to begin once again.

This moment, a somewhat comedic respite from the drudgery of war, helps align the film’s more specific political alignment, not for or against either side, but undoubtedly against the very ideologies that have resulted in such conflict and division. This alignment is further evidenced by the film’s closing lines, which mourn the loss of life on both sides, and dedicate the film to their memory. Despite its significant emphasis on humanising the North, such focus is not done so to provide a propagandistic communist version of events, but instead is done so to undo the decades of dehumanisation projected at the North. The film therefore attempts to reject the imported ideologies which are responsible for the division of the Korean peninsula, and to allow a space for coming to terms with the trauma over such division, free from the ‘us versus them’ warmongering of other countries.

This attack on ideology can also be seen in other films which deal specifically with the Korean War. In The Taebaek Mountains (태백 산맥, 1995) the tumultuous build up to the Korean War is shown mostly through the perspective of a teacher who doesn’t wish to align with either side. The film ends with the destruction of the village occupied by the North, while the teacher walks horrified through flaming streets and a shaman, who had previously been prevented from practicing, performs a burial ritual. The linking of an anti-ideological stance with that of tradition signals the imported nature of the two ideologies, with the capitalists and the communists both being driven to acts of oppression and violence upon the people due to their unquestioning fealty to their respective structures and mindsets. Similarly, the grand oppressor of the island village in To the Starry Island (그 섬에 가고 싶다, 1993), in which a son attempts to bury his father at his home island but is stopped from doing so by the other islanders, is not any particular person, but ideology. The finale of the film finds South Korean troops, disguised as Northern soldiers, interrogating the inhabitants and filtering them off into separate camps of comrades and traitors. It is then revealed that the event was a ploy intended to weed out communist sympathisers from the community, and that an islander had been interrogated by the Southern army, following claims that there were communists on the island. Despite the objections from the local teacher, who argues that the villagers do not follow either ideological alignment, and were in fact pressured into their acts of allegiance, the soldiers massacre the ‘communist’ villagers. The very act which halts the father’s body from being returned to his homeland is therefore an act which was coerced, a betrayal of others in order to prevent further harm to the self. This clear parallel between the father and the ‘communist’ islanders thereby emphasises the tragedy of ideological warfare, which expects all to fall in line or else be considered an enemy. These films therefore attempt to unpick and undo the decades of indoctrination, and instead foster a recognition of the many tragedies committed throughout the Korean War under the justification of ideological differences. In doing so there is a longing to mourn and contemplate the long-lasting traumatic effects such tragedies have inflicted upon society.

A Single Spark and Film as Mediator of History

A Single Spark arrived at the intersection between the maturation of this emphasis on trauma and politics, and the wider transformation of the South Korean film industry into the mainstream, genre-heavy cinema for which it would later come to be known.[15] Moving beyond the more general representations of historic trauma that had become integral to certain strands of South Korean cinema during this period, Park Kwang-su instead sought to examine film’s relationship to history through an exploration of Jeon Tae-il. The film thereby attempts to bridge the gap between history and the present, by way of including a parallel narrative concerning a political writer who is attempting to write a biography of Jeon Tae-il’s life. The film therefore positions itself not just as a biographic film, but also a film about the very act of constructing a biography. It makes an explicit divide between the two narratives, the historical events portrayed in black and white, and the writer’s attempts to understand the history are shown in colour. This specific examination on biographic impulses is foregrounded at the film’s conclusion, where Jeon Tae-il’s immolation is shown twice, first as a moment of history – chaotic and frantic – and then it is shown as portrayed by the writer. This second time, the act of protest focuses solely on Jeon and his commanding presence as he is consumed by the flames, and in doing so it visually represents the way in which biographic works are beholden to a subjective interpretation of events.

Jeon Tae-il is no longer a worker who protested injustice, he has now become a symbolic martyr of the continuing struggle for workers’ rights and freedom from oppression. The film emphasises this in its closing shot which sees the writer witness to his book being carried by a young student, who is then revealed to be played by the same actor who re-enacted Jeon Tae-il’s life in the film. This discussion of biography and history therefore invokes a wider examination of film’s ability to mediate historical events. Kim Kyung Hyun acknowledges this in their analysis of the film, stating:

“While the film casts doubt on the authority of its narrator, who romanticises [Jeon’s] death and dramatizes its significance, the problem remains that the actual death is also a fictional representation, by Park Kwang-su”.[16]

This observational approach to image, re-enactment, history, and the present is found throughout the film. Though such observations are framed within the film’s narrative through a focus on writing, a medium even more divorced from reality than the photographic image, the film nevertheless aligns this biographic examination in parallel with an examination of film’s ability to discuss and disseminate history. Beginning with footage of a protest march in support of workers’ pensions, followed by a black and white shot of Jeon Tae-il setting fire to his book, and finally another colour shot depicting the writer working on his biography at night, the film establishes its multi-layered approach to history and reality: the initial documentary footage of the protest gives way to the re-enactment of an event, and then moves onto the entirely fictional narrative concerning the biographer. At the same time, the relationship between these images highlights the different histories at play. The protest footage, occurring after the historical events that inspired the film, is also positioned as the spiritual inheritor of Jeon Tae-il’s act of resistance against oppression. But it is footage of the re-enactment which follows the protest, not the actual event itself. Though no footage of the original event exists, there are countless other historic photographs which could have connected the contemporary protest with the actions of the past, for example the photographs of Jeon’s funeral. The film, therefore – in opting to foreground its own version of Jeon Tae-il’s act – reveals its desire to position film as a central mediator between history and the present. At the same time, it acknowledges that film’s relationship to history must be one of subjective emphasis, of selective inclusion and omittance, and of an unavoidable glorifying of certain actions and events.

Jeon Tae-il

Conclusion

Can film bridge the gap between history and the present? In many ways, film’s fragmentary nature, its montage of disparate times and places, brings it closer to the past as we experience it. As Walter Benjamin put it: “The true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognised and is never seen again”.[17] Heraclitus, the esoteric and often confounding philosopher of Ancient Greece, perceived the world as being in a constant state of flux, forever changing. Speaking of this flux, he put forward that:

“The river

where you set

your foot just now

is gone –

those waters,

giving way to this,

now this”.[18]

For Heraclitus, then, the constantly shifting nature of the river meant that it was impossible to stand in the same river twice, as each time you enter it the river would have changed. Just as with the river, where each interaction with it is unique, so too do we experience each moment only once in its totality. After this, our recollections, memories, and experiences of the past are fragmentary, and fundamentally altered from the original experience. In acknowledging the past as something that can never be reclaimed or relived, only recontextualised, it is possible to understand film’s tendency to interact with and re-enact historical moments.

This tendency is further bolstered by film’s ability to, as André Bazin puts it, embalm time. The initial events that inspire a film may not be captured, but a film’s attempts to interpret and recreate those events are mechanically reproduced and thus able to be experienced again and again. Further to this, Bazin argues that there is an indexical element to the photographic process, which allows these historical re-enactments to become historical objects in themselves.[19] These re-enactments therefore exist as historical objects which vaguely point towards a less concrete actual history, but for the most part become a simulacrum, inhabiting their own reality. The history they present to us has the potential to overpower the actual historical events they depict.

A Single Spark portrays an awareness of the fragile nature between biography and embellishment on a level which has rarely been seen in South Korean cinema since then. It both fulfils the initial promise found in the politically motivated independent cinema of the 1980s and signals the subsequent decline of this motivated spirit as the South Korean film industry moved further into its support of mainstream entertainment and focus on box office numbers. Only Jang Seon-wu’s A Petal (꽃입, 1996), released the following year, embodied the same multi-faceted approach to collective trauma and subjective history, though it lacked the specific focus on the ways in which film can weave both concepts together. A Single Spark therefore stands as a historical marker in its own right, evidencing the potential capabilities for film’s role as an active investigator of its own relationship to society, ideology, and history. Unfortunately, that potential remains unfulfilled to this day.

[1] Cummings, Bruce (2005) Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History, pp. 375.

[2] Most notably, Jeon’s mother founded the Cheongye Garment Workers’ Union following his death. Jeon remains a symbol of resistance against oppression even today, as shown in the recent events which celebrated the 50th anniversary of his death.

[3] The other being “[democratic protestor] Kim Dae-jung’s mass support”, pp. 376.

[4] Yushin, lifted from the Japanese term Isshin, meaning ‘reform’.

[5] Cummings, pp. 377.

[6] Who was, at the time of the assassination, the director of the KCIA.

[7] Sometimes these genres were combined, as in Suddenly in the Dark (깊은 밤 갑자기, 1981).

[8] Notably, despite these affairs the woman remains with her husband at the end, highlighting the film’s use of affairs not as representative of a new found sexual freedom for women in society, but instead as chances for erotic scenes to draw in spectators.

[9] At the time of writing, there are eleven numbered entries in the Madame Aema series.

[10] Shin Kang-ho (2006), pp. 299.

[11] The Night before the Strike was a major success in terms of independent cinema, and its success was despite attempts at its suppression by authorities. Rather than cinemas, its major sites of exhibition were university campuses.

[12] The most common names associated with this category are Park Kwang-su, Jang Seon-wu, Cheong Ji-young, and Lee Myeong-se. As with all categorisations such as this, it is important to acknowledge their tenuous nature and not allow the category to remove the individual films and filmmakers of their specifics by subjugating them to a broader collective analysis.

[13] The name is a joke, 판촉(Pan-chok) literally meaning ‘promotions’.

[14] This is not to say that all political cinema made this shift, rather that there is a clear diversion made during this period to examine political concepts through past events

[15] The groundwork for a mainstream cinema had been established by films like Mister Mama (미스터 맘마, 1992), Two Cops (투 캅스, 1993), and The Five Tailed Fox (구미호, 1994), and this approach would only be further cemented following the release, and success, of The Gingko Bed (은행나무 침대, 1996).

[16] Kim Kyung Hyun (2005), pp. 119.

[17] Benjamin, Walter (2005), pp. 247.

[18] Heraclitus (2003), pp. 27.

[19] It is this very indexical relationship which allowed Bazin to claim that the surrealists were able to create ‘an [sic] hallucination that is also a fact’ through their employment of photographic images. Bazin (2005), pp. 16.

References

Bazin, Andre. “Ontology of the Photographic Image” in What is Cinema? Vol. 1. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History” in Illuminations. London: The Bodley Head, 2005.

Cummings, Bruce. Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York/London: W.W. Norton, 2005

Heraclitus. Fragments. New York/London: Penguin Books, 2003.

Kim, Kyung Hyun. The Remasculization of Korean Cinema. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2005.

Shin, Kang-ho. “In Search of a New Cinema and Alternative Cinema” in Korean Cinema: From Origins to Renaissance. Seoul: Communication Books, 2006.

Author Biography: Connor McMorran is a musician, artist, and occasional independent scholar who received their PhD in Film Studies from the University of St Andrews in 2019.

This original feature article was written for New Korean Cinema, Liberating Cinema Film Series 2021.