The Goat Horn by Metodi Andonov in the Context of Classical Bulgarian Cinema

By Alexander Donev

Metodi Andonov, the director of The Goat Horn (Козият рог, Bulgaria, 1972), entered the cinema in the early 1960s. This particular period of socialist film production in Bulgaria is characterized by the contradictory nature of the cultural policy and the anti-Stalinist course that began in the mid-1950s. Gradually it became increasingly clear that the denial of the cult of the personality of the supreme communist leader was an element of the internal struggle for power rather than a real change in the party line. That is why here it is important to emphasize that Metodi Andonov is not a dissident. His first experience as a film director was in 1965, directing а three part TV-movie, based on the contemporary crime story by the Bulgarian writer Bogomil Raynov, who is very close to the communist leadership. At that time the 33-year-old Andonov already had a near decade long successful career as a theatre director. He proves his abilities as an inspired and insightful interpreter of Russian and Bulgarian dramaturgy. In his original productions he combined the Slavic mentality with some of the theatrical principles of Brecht, who was the only modern stage writer and director recognized at that time by the ideological censorship in Bulgaria.

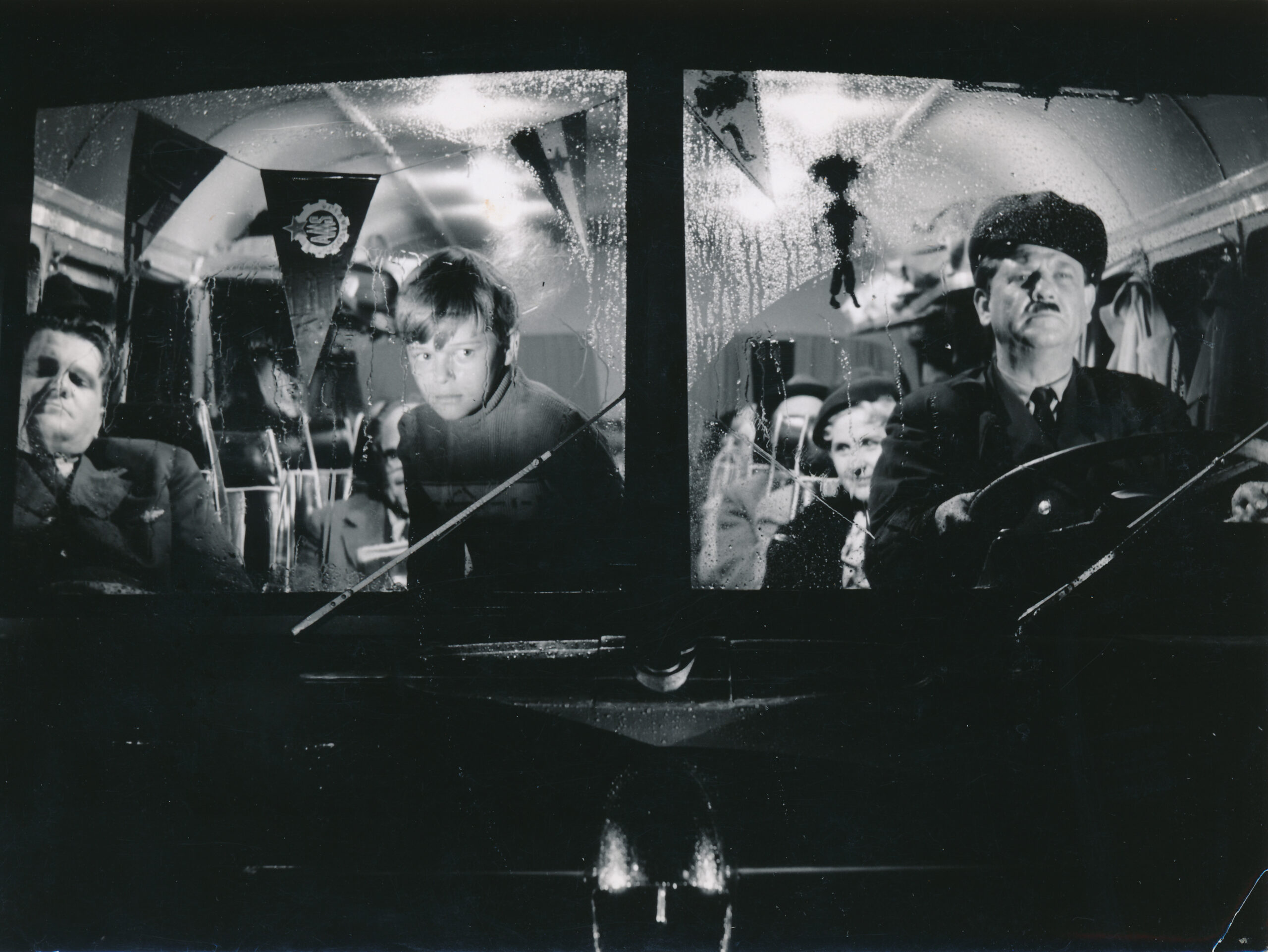

Andonov’s film debut is the contemporary existential drama The White Room (Бялата стая, Bulgaria, 1968). It tells the story of a thirty-year-old scholar who fights for the freedom to seek the truth in science on his own, without regard for the authority of older colleagues or communist ideology. Paradoxically, the film is again based on a novel by Bogomil Raynov, known in the 1950s as one of the agents of dogmatism and repression against cultural figures. The White Room was the first Bulgarian film with the monological structure that was trendy at the time, breaking the strict chronological sequence of the narrative, putting the emphasis on the stream of consciousness of the protagonist. A method introduced into literature by the modern French novel, and into cinema by the films of Bergman, Fellini, and Antonioni at the end of the 1950s and the early 1960s. Andonov’s next film, There’s Nothing Better Than Bad Weather (Няма нищо по-хубаво от лошото време, Bulgaria, 1971), was a screen adaptation of a spy novel by Bogomil Raynov about a Bulgarian character, a communist version of James Bond. This series of novels was published in all Eastern Bloc countries and became extremely popular especially in the Soviet Union. Andonov proves his capabilities as an agile film director, capable of building a suspenseful plot with convincing psychological characters and original visual and editing choices.

It was his ability to work in a shortened timeframe, efficiently and at a high artistic level that led Metodi Andonov to the realization of The Goat Horn, considered by many to be the best Bulgarian film of all time. This film appeared somewhat accidentally, as even before the audience and critical success of There’s Nothing Better Than Bad Weather, Metodi Andonov received an offer from the management of the state-owned Feature Film Studio to make a film based on a script he chose himself. This is a rather unconventional proposition for the socialist production system where, especially in the heightened political climate following the events of 1968 in Czechoslovakia, every film was subject to strict scrutiny at every stage of the production process, from the initial idea to the final cut. The reason for this is that, at the end of 1970, there were funds left in the budget of the state film studios which, if not invested in a new production, would be returned to the budget, and this was not a good attestation for any socialist business executive. The amount was not significant, sufficient only for low-budget production, which is why all the famous directors refused to take up the offer.

Andonov hesitates between two stories by the Bulgarian writer Nikolai Haytov from his collection of short stories entitled Divi razkazi (Wild Stories), published in 1967. In the end he chooses ‘The Goat Horn’. The most authoritative figure in Bulgarian literature at the time, the 60-year-old writer Emilian Stanev, had a very interesting assessment of the potential of this story. He says to his colleague writer, twelve years his junior: “You have stumbled upon a very original plot, there is no second like it, it rarely happens. The plots are usually repetitive, especially the love ones. There are 5-6 schemes, one triangle and that’s it. A “goat horn” is something pure, untouched by anybody. You can write on this plot a novella, even a real novel, and you’re stuck in four pages. You have to write something much longer before someone steals your stuff.”

From my observation, Andonov found a source of inspiration not only in the literary material, but also in Ingmar Bergman’s film The Virgin Spring (Jungfrukällan, Sweden, 1960). Of course, this is a research hypothesis I propose insofar as there are no personal testimonies or memoir records. The evidence lies in a comparative study of the films themselves. Bergman’s film is also a rape and revenge drama. It is set in medieval Sweden, an epoch comparable to the 17th century in the Bulgarian lands. It is a tale about a father’s merciless response to а rape and murder – in Bergman’s film of his young daughter, in Andonov’s of his young wife. The similarities in visual style and the expression of black and white cinematography are also significant. While Bergman’s film was first shown unofficially in Bulgaria only to students and cinephiles much later Metodi Andonov had the opportunity to travel abroad. He had shot scenes from his spy film There’s Nothing Better Than Bad Weather for several weeks in West Berlin in the year before he made The Goat Horn. I dare to believe that he had a very clear idea of how the Bulgarian plot should be realised, so that the story would be highly evocative, without seeming brutally naturalistic and regional, but with universal implications.

As film concept The Goat Horn continues the discussion of key themes in The Virgin Spring such as feelings of guilt, vengeance, the questioning of faith and sexual innocence. A very strong motif in both films are the fathers’ possible feelings of incest towards their daughters. Another important issue is the conflict between paganism and Christianity more clearly elaborated by Bergman and probably not as obvious in Andonov’s film. Actually, both fathers stage their killings as ‘ritualized pagan vengeance’. In both films the water is a very important symbol, at the same time Freudistic but also in the meaning of the Christian religion.

However, two types of interpretations of the film The Goat Horn were the most relevant for the Bulgarian audience of the time. On the one hand, it could be read as a kind of veiled critique of communist ideology and especially its methods of educating the ‘new man’, particularly characteristic of the 1950s and 1960s. The basic principles of this educational theory are a total break with the past if it contradicts the realization of the ideal, hatred of the enemies of communism and ruthlessness in their destruction. These are also the emotional structures that the father wants to build in the character of his daughter, raising her as a man and teaching her to kill. Another much more elementary interpretation, however, which is perceived quite directly and determines the film’s mass viewing success, is the serving of nationalistic attitudes. These are fuelled by memories in history and literature of five centuries of Ottoman rule, whose contemporary representatives are recognized in the neighbouring Turkish state and the significant Turkish-speaking and Muslim minority in Bulgaria.

We can consider that what Metodi Andonov himself in part tried to do, through his film, was to join a discussion taking place unofficially in Bulgarian intellectual and political circles. It refers to the line of the ruling and only party in the country at that time, the Communist Party of Bulgaria, aimed at repressive and forced integration of Muslims – Turks and Pomaks – into Bulgarian society. The far-reaching strategic goal of the party establishment was, on the one hand, the complete unification of all socialist citizens and, on the other, the declaration of Bulgaria as a one-national state and the nation as homogeneous – in an ideological and ethnic sense.

Metodi Andonov ultimately finds a sufficiently impactful and compelling form to convey a vividly humanistic and universally valid message on all of the controversial issues his film raises. And this message consists in faith in the all-conquering power of love, which has the most profound energy for individual transformation and for overcoming the contradictions between people.

Author Biography: Alexander Donev is Associate Professor of Screen Arts at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and the National Academy for Theatre and Film Arts, Sofia. He is a Member of the Bulgarian Film Academy and the European Film Academy.

This original essay was written for Classical Bulgarian Cinema, Liberating Cinema Film Series 2021.

Liberating Cinema would like to thank The Bulgarian National Film Archive for providing the film images used in this essay.