Liberated Cinema: Karađorđe, or The Life and Deeds of the Immortal Vožd Karađorđe

By Božidar Zečević

Last week marked 110 years since the premiere of the first Serbian feature film Karađorđe (The Life and Deeds of the Immortal Vožd Karađorđe, October 1911) directed by Čiča Ilija Stanojević and produced by the first Serbian film producer Svetozar Botorić. This anniversary, though not exactly ‘round’, is significant for the spirit of liberation and rebirth of the Serbian world, which we see again happening today. It is worth pointing out the fact that the birth of Serbian cinema took place at the height of a decade which is now referred to as ‘the golden age’ of progress and regeneration in the years between 1903 and 1914 and which is again studied as a kind of socio-political, economic and cultural miracle, quite expectedly giving birth to the artistic film as a colossal sign of the new era. Just over 100 years (and perhaps the most difficult 100 years in our modern history) has elapsed since Serbia was graced by God with the greatest blessings on the eve of the nation’s perils of war, its affliction, and resurrection from 1912 to 1918. “The Serbs built their country by their own inborn strength in which all government lies in the hands of Serbs, and not foreign occupiers, as is the case with other liberated countries in the Balkans” wrote Jovan Skerlić at the time as perhaps the most influential figure of this time. “The people in Serbia raised in the spirit of freedom for freedom, politically mature and without a big brother, governs itself and built a country neither dynastic nor class-based but exclusively its own, of the people and for the nation” (1910). This is also the first characteristic of the epoch in which the liberated cinema was born. It is certainly not in vain for us to highlight: The significance of this statement is that it represented the dominant interpretation of the Serbian national idea in the period 1903-1914; it could not be more succinctly, picturesquely, and clearly expressed than that” (Miloš Ković).

The Cinematic Birth of a Nation

The title of this article is not accidental. Liberated Cinema, indeed. The spirit of liberation predominates in the film just as it does in the apotheosis of the new birth of a nation under the leadership of Karađorđe, that is, in the magnitude, drive, and inspiration in which the moving images emerged. “Starting from literature, and from art, music and history, geography, the history of philosophy…all the way through to musical folklore and every other form – all that was a part of an unusual and hurried line of action. Whatever was touched turned into green gold, a good coin” (Branko Lazarević). Lazarević’s quip applies naturally and especially to film, which from its birth to the present day remains crucified between art and industry, aesthetics and the market. What is, however, staggering is the piece of the puzzle added by Dimitrije Đorđević, the greatest historian of the epoch: “While 144 industrial enterprises were founded in Serbia between 1873 and 1906, from 1906 to 1911 284 new industrial firms were opened, double the amount in a sixth of the time. Industrial production increased sevenfold in the same period”! And all this happened in the environs of Belgrade’s Terazije Square where you could find twelve cinemas operating in the first half of the last century (none of which remain today!) and where Svetozar Botorić’s “Hotel Paris” dominated with the first permanent cinema among the Serbs (1908). “The newspapers advertised French cognac and plum brandy, Jamaica rum, Swiss cheese, Italian sardines and the pianos flügel… The Hotel Paris proudly proclaimed to be the home of Perisan chess”, Đorđević writes as he describes the crystal ambient in which some way through mid-1911 that historical lunch took place when Botorić, the owner of the Hotel Paris, called in the famed actor Čiča Ilija Stanojević and partner of the state ‘Klasna Lutrija’ Ćira Manok in order to make the following proposition:

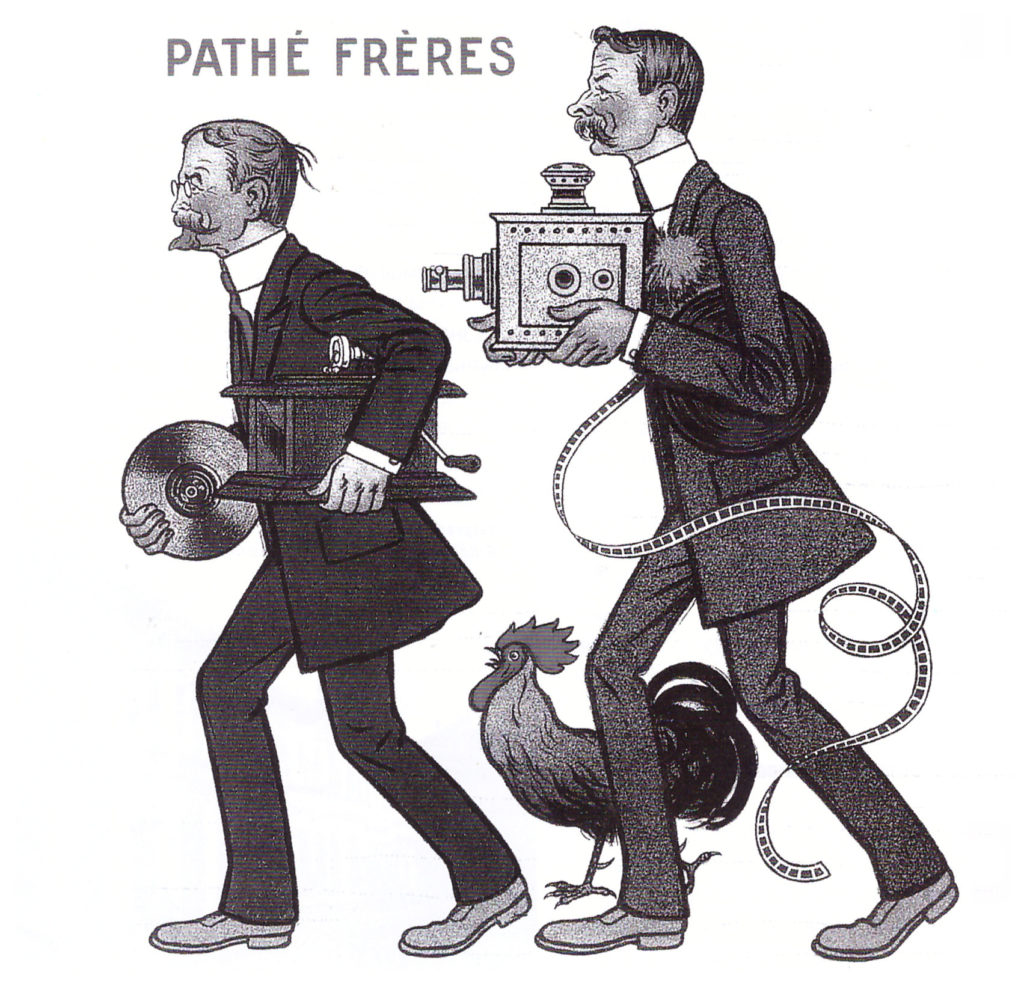

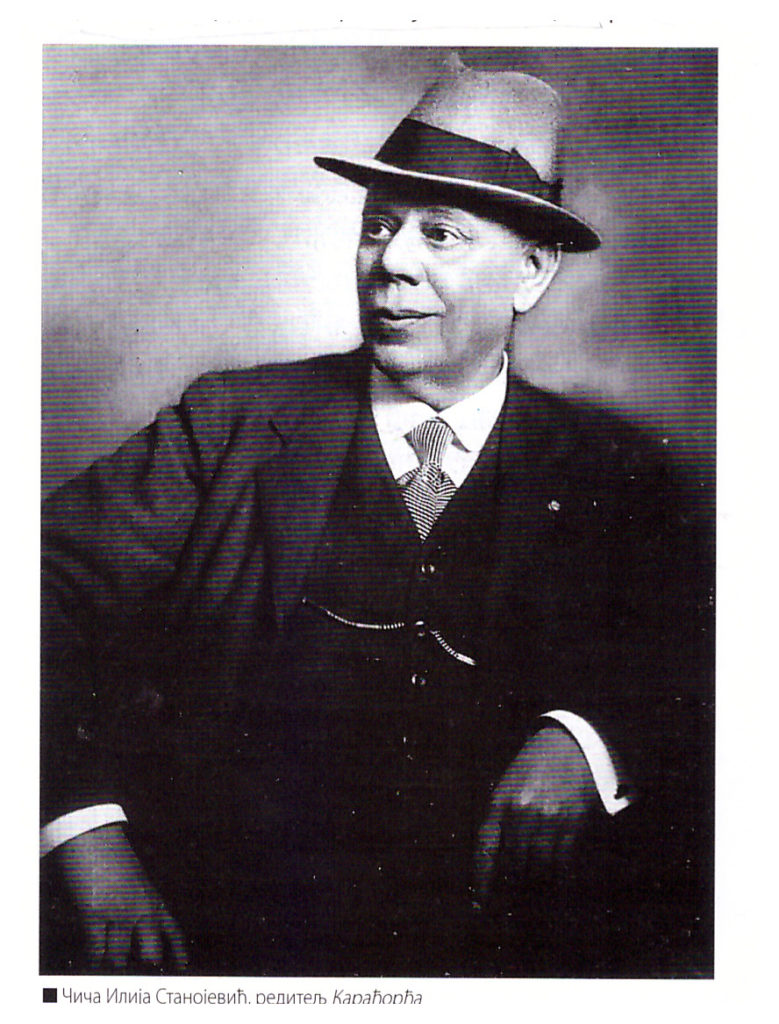

“Pathé sent me an outstanding cinematographer with the call for us to make Serbian films. Let us stand together then and establish “The Serbian Film Production Association”. You serve as the executive and film director, and I will be your producer. Then Botorić told Čiča Ilija Stanojević that he and Ćira Manok came to the conclusion that one great feature film should be shot and that Manok and Savković were already putting together a screenplay for the film” (Dejan Kosanović). But who really were the people who in 1911 created the first Serbian film production and one no less connected but with one of the most powerful European production houses Pathé Frères, for whom Botorić was the chief representative for Serbia and Bulgaria? The same Parisian company assigned cameraman Louis De Beery (actually Hungarian going under the surname Pitrolf) to shoot films around southeast Europe and he is the first cameraman of Serbian films of which fifteen documentary and two feature films survive to our day – Karađorđe and Ulrih Celjski and Vladislav Hunjadi. The Aromanian Ćira Manok was a renowned Belgradian entrepreneur and Botorić’s partner in various ventures. Svetozar Botorić himself was a first-class businessman and resolute patriot (which in the end cost him his life in 1916 in the Austro-Hungarian camp Nežider), one of the more visible members of the People’s Radical Party and a personal friend of Nikola Pašić, and his hotel unmatched in the whole Kingdom was for years the unofficial headquarters of the ruling party. And finally, Čiča Ilija Stanojević, one of the emblematic figures of old Belgrade, an outstanding Serbian actor, director and writer, here especially important for us is his role as the first Serbian film director who managed to devise, compose and realize our first artistic film. His undertaking showed itself to represent a serious artistic and cultural mission. The new art of the cinematograph, still held under the rubric of folk entertainment and fairground attraction, had to prove itself worthy of the national pantheon.

The First Film Author

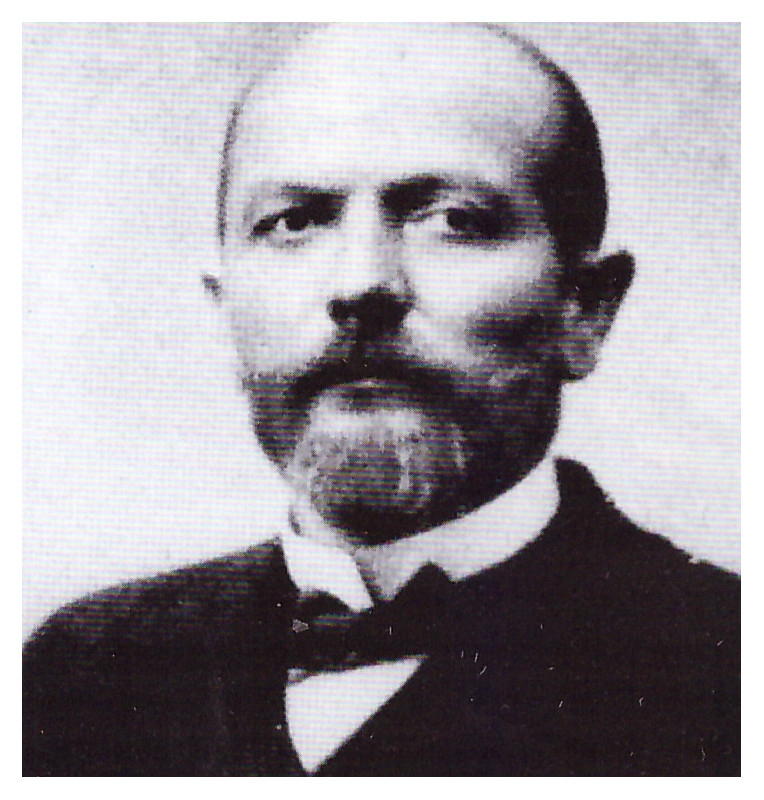

It became immediately evident that Čiča Ilija knew well that every cinematic work required two main ingredients. The first of these ingredients is dramaturgy, namely the organization of the artistic material according to certain poetic principles. The second is film direction, the organization of time and space as one whole (under which fall a voluminous number of steps and specific techniques – from the camera for which Čiča Ilija had the help of the adept professional De Beery, a sure hand and one who knew how to master a shot, to working with the actors, the crème de la crème of contemporary Serbian theatre). At once he thwarted the attempts of ‘sponsors’ and ‘investors’ who had created ‘their own film’, ignored Manok and a Father Savković, and took the matter into his own hands (something which does not come easy even for a majority of our directors working today!). At his disposition he had the works of Milan Ć. Milićević, the incomplete biography of Karađorđe by Milenko Vukićević, the ‘thin’ drama of actor Miloš Cvetić and of course The Beginning of the Revolt against the Dahijas by Filip Višnjić from Vuk Karadžić’s collection of Serbian epic poetry with its series of reverberations still living in national tradition. According to all the rules of dramaturgy of the time he succeeded in composing the film through 16 tableaux (or at least these are the ones which remain after the careful and scrupulous reconstruction of the film by Aleksandar Saša Erdeljanović, the director of the Archive of the Yugoslav Cinematheque who discovered two thirds of Botorić’s films with Nikolaus Wostry in the Austrian Film Archive, and subsequently the restoration of the material in foreign film laboratories and in doing so acquired recognition of national significance). The saga of Karađorđe thus received a certain cinematic wholeness, verily portraying the important events of the people’s liberation. When it comes to the actors, the theatre pleiad of the day led by Milorad Petrović, one of the greatest Serbian actors of all time and when it comes to film the first leading man of Serbian cinema. bowed graciously before their audience in Belgrade on the 23rd October 1911. His Karađorđe is strong in build, dark in appearance and steadfast in will just like the Vožd himself was; nothing from his biography is kept hidden, no part is covered up; not one resolute gesture is repeated. He weaves his character out of the details. The Vožd’s robust and intimidating constitution is complemented by his embodiment of soulful Serbian home keeper who knows how to laugh from the heart and then falls again into misery and affliction. In their work Karađorđe was thoroughly studied both cinematically and historically. In him all the decorations bestowed on him by the Russians The Vožd’s temper makes all his Russian medals tremble on his chest or it all rests in the elusive dream in the hut of Radovanski Lug as his death approaches. He shows great pleasure after the victory at the battle of Mišar. The Vožd becomes at once friend, governor, godfather, he is Serbia of his and our own time, which escapes the clutches of evil and frees itself on account of its own efforts. And so, it is in this way, by the means of the new art on the world horizon, that our own cinematographic pantheon emerged.

Liberated Cinema

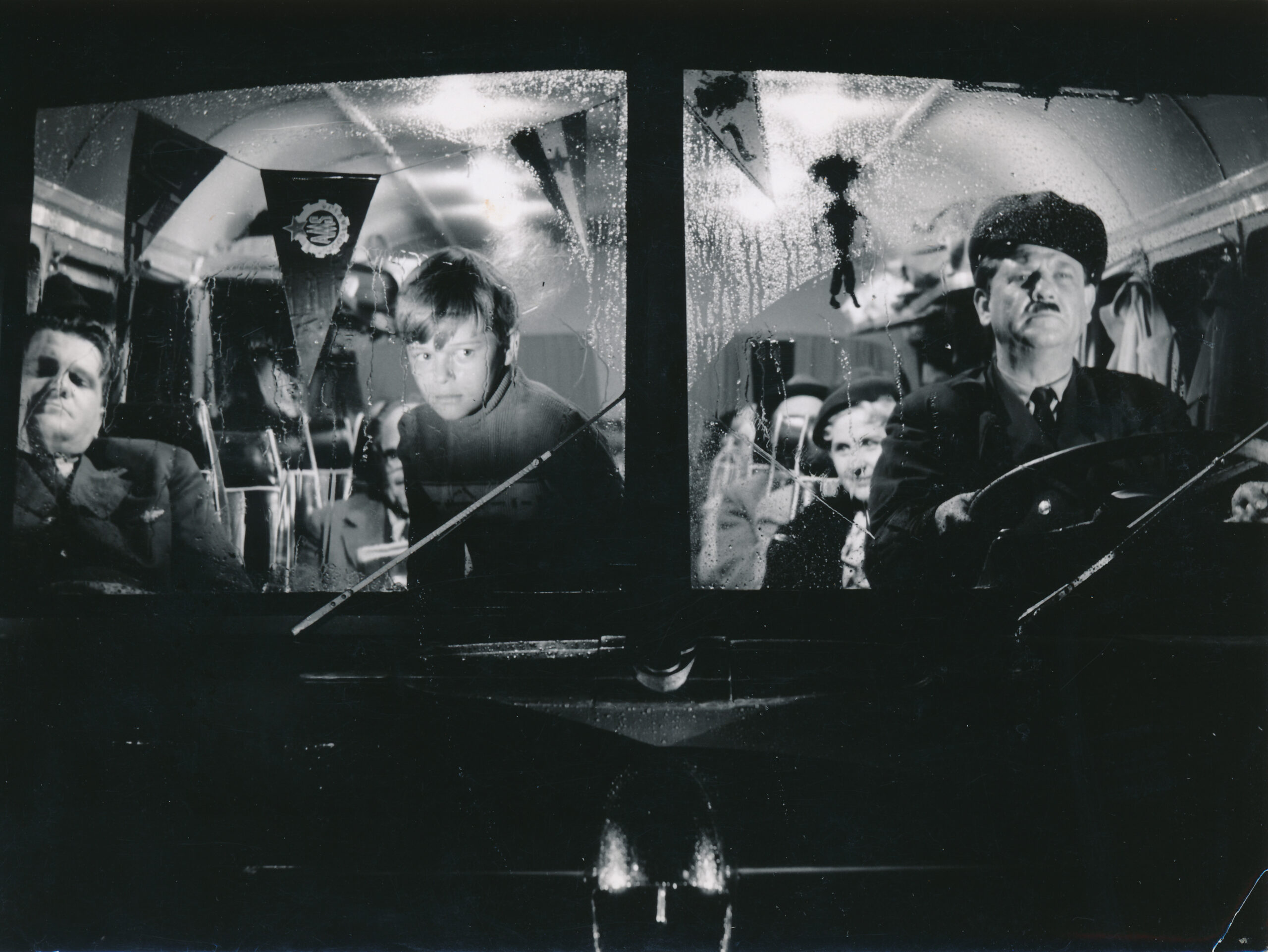

It all happened once upon a time in the house of film, in the theatre of the Yugoslav Cinematheque several nights before the new premiere of Karađorđe, on the Meeting of our Lord in the Temple (Sretenje) in 2004. There were no excessive displays, no ephemeral commotion, no television presence (but the television just the same deserves every commendation for broadcasting the film the same night). Rather, in the festive silence of the small auditorium the double of every of one of us Karađorđe performed in a historical film which time wearied but which it also fortified, bestowing upon it great honour. Though it is difficult to precisely evaluate the unity and structure of this film which appears to be lacking around twenty minutes from the original version, the fact remains that (in a ratio of 11:5!) exteriors dominate, meaning scenes shot and structured outdoors, which is a quite rare feat for the time given that everywhere else in the world precedence was given to shooting in studios. The overwhelming presence of daylight and shadows, without ‘blending’ and additional artificial lighting (‘the diffuse overcast lighting’, a masterstroke of De Beery’s work), the visages of the Sava and Danube rivers, real boats and boatmen, the cawing of Belgrade crows, the blows of the south eastern wind (what we call Košava) sweeping through the shot – imbue the film precisely with that Bazin-ian dimension of the realistic and unique vision in which Karađorđe, man and myth, becomes filmic possibility. The film also stars one incidental Belgrade canine – just like in The Coronation of King Peter I of Serbia seven years earlier – whom the cameraman ‘hunts’ in one uninterrupted take of the Battle of Mišar (shot in Banjica, the site on which the Military Medical Academy now stands); he feels the presence of reality and does not want to let it drop. The shot built according to depth and diagonal composition reveals an innovation of the film author while the flat and the lateral principle, the cornerstone of the film d’art, the leading movement in the ‘artistic film’ of the day, is avoided at all costs!

The “photogeny” of Karađorđe is its greatest cinematic quality. The highest film standards of the era, which Louis Delluc formulated as the “hidden essence of film” or the property of human faces and objects that through the use of moving pictures lead to a revelation of the soul through details, internal emotions, visions of the miraculous, the magical and the dream, liberating cinema in every way from the theatre, which is its chief enemy, were realized in the venture that is Karađorđe.

The finale of Karađorđe tells us much about the film’s conceptions about direction as well as its directorial style. The same group of jubilant rebels stand together in a majestic ensemble. An angel descends and bequeaths Karađorđe with a laurel wreath. The Vožd and his insurgents, until a moment before people of flesh and blood, appear now as living monuments of time. Through one cut reality is transfigured into an apotheosis, a legend, a myth. This ‘factor of irreality’ (Eisenstein’s term) accomplished entirely in the spirit of the film code of the time is a great surprise. Therein cross the historical and poetic features of the work. The film becomes the man, the man his double, entirely in the spirit of the epochal idea articulated by Edgar Morin.

The comedian, Bohemian and Skadarlija’s ‘one-man inventory’, as Čiča Ilija remains known in Belgradian folklore, turns out to be wholly equal to the greatest directors of his era (the unfortunate fate of our ‘Uncle Ilija’ afflicted also one of the greatest minds of the epoch Mihailo Petrović Alas whose street is still called by his nickname ‘Mika Alas’). That same Ilija Stanojević is incomparable in his direction of well-composed medium totals at the time when the many mass scenes of Giovanni Pastrone and D.W. Griffith appeared as a lifeless stack of dolls. One only needs to take, for example, sequences from Cabiria (1914) and Intolerance (1916) where the scene demands the individual participation of each actor in the shot and then compare it with Stanojević’s Karađorđe! On the one side monumentalism, theatrical movement, an operatic choir, the first shot the same as the last, on the other an ensemble of actors where each one carries out and fulfills his filmic mission. In deep focus, the action takes place on the first, second and third level of the frame! The direction is composite, individual, far from theatrical, because this kind of organized crowd would not even be possible in the theatre. Play it back one hundred times and you will be convinced: thirty excellent actors of the theatre now play in something else, a film, and Stanojević instructed each one of them, because their medium was different – the artistic cinematograph of the twentieth century! I often wonder what would have happened if back then in 1911 our ‘Uncle Ilija’, as Botorić had already envisioned it, became ‘Elia Stanojević’, which would mean the same as when we say Elia Kazan or Erich Von Stroheim? But it did not come to pass. Čiča Ilija went back to theatre, to Skadarlija, and today they throw around time worn anecdotes about him from the cobbled streets and the theatre bifes of old Belgrade.

Author Biography: Božidar Zečević is the leading Serbian filmologist, film historian, dramatist, screenwriter, director, university professor of film analysis, and the founder and editor-in-chief of the film journal Filmograf.

This original essay was written for KARAĐORĐE: The 110th Anniversary Symposium of The First Serbian Feature Film with HRH Crown Prince Aleksandar of Serbia on 23rd October, Liberating Cinema Film Series 2021.