Tito and Me: A Brief Journey Through the Movies With Josip Broz Tito

By Fedor Tot

Goran Marković’s Tito and Me was released just as Yugoslavia begun to collapse, broaching the cult of personality that had built up around the country’s deceased leader, Josip Broz Tito. Tito had led the country out of WWII, having defeated both the Nazi occupying forces and Chetnik monarchists, establishing a post-war socialist Yugoslav state. Disagreements with the USSR led to Yugoslavia being expelled from the wider Communist Eastern Bloc in 1948, but despite such challenges, Yugoslavia managed to chart its own course of socialism, aided in part by Western funds but also by Tito’s sharp diplomatic senses. In return for this, he was declared President for Life.

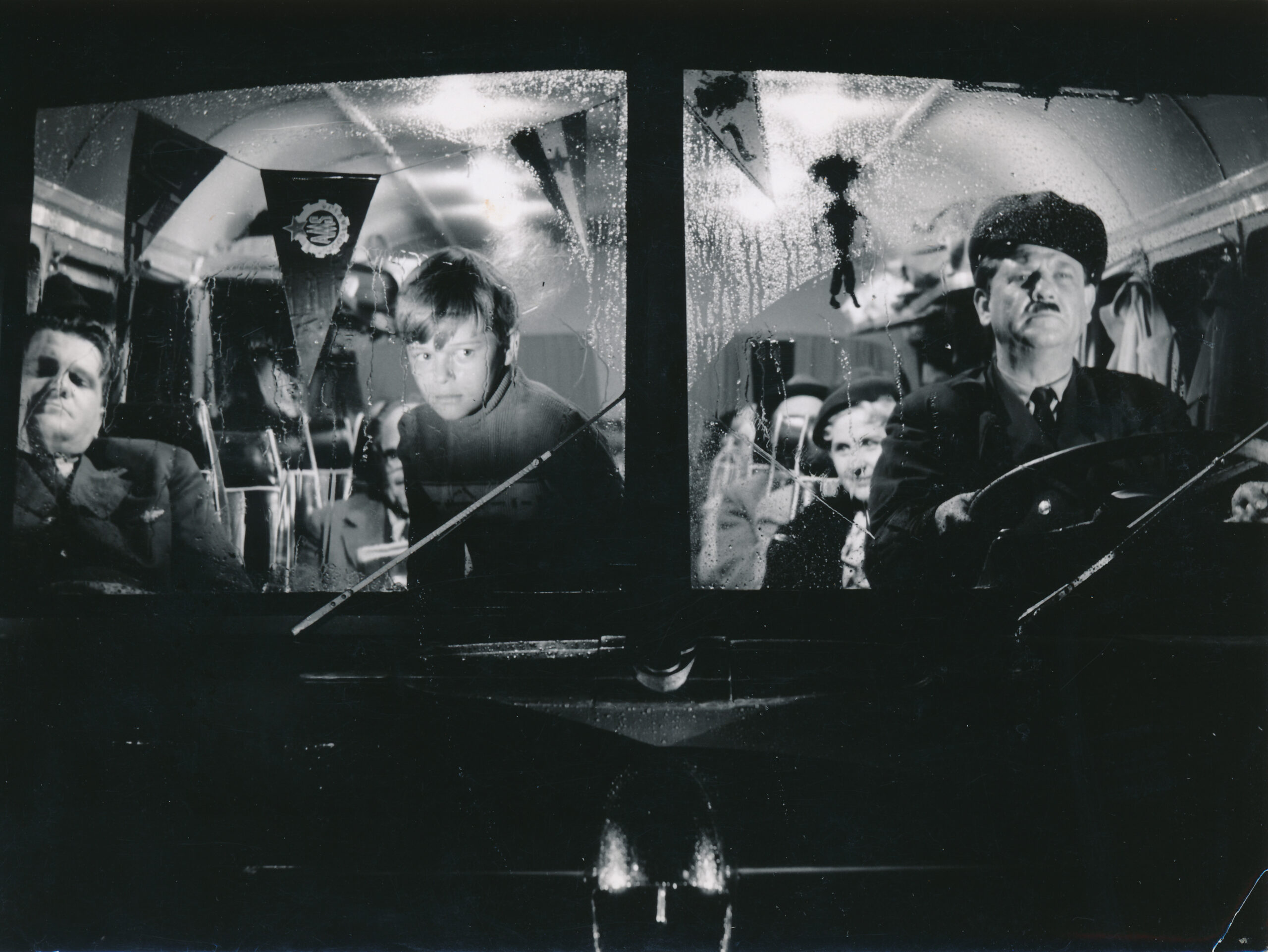

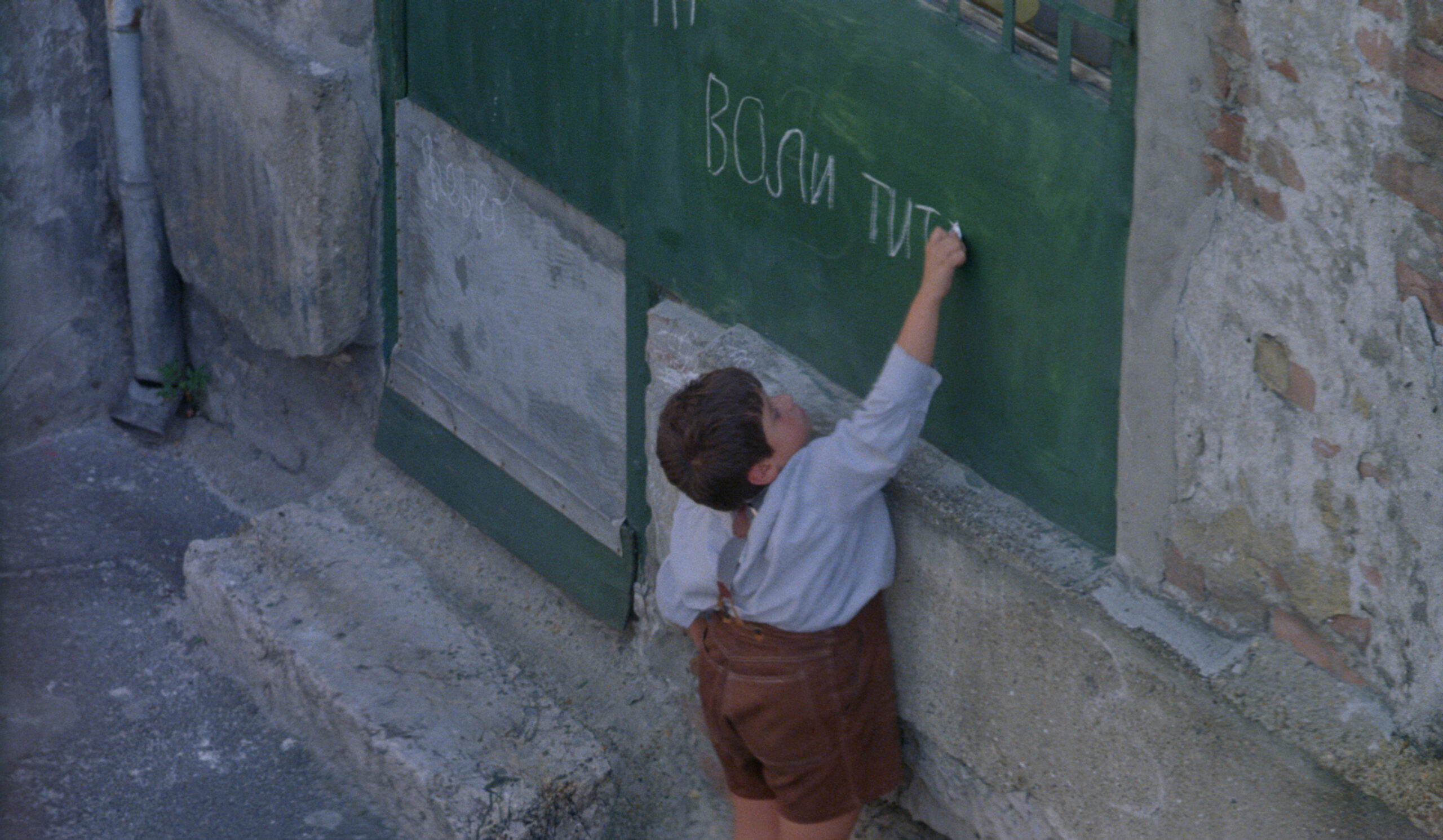

His death in 1980 marked a monumental change in the Yugoslav state, creating at least in part some of the factors that led to the country’s breakup only a decade later. Artistically, his death opened up another change: a gradually loosening of what was and wasn’t acceptable to depict onscreen. In Tito and Me, Marković presents Tito as an apparition – the fantasies of an obsessive young boy, idolising him more than he does his parents. We follow Zoran (Dimitrije Vojnov) on a pilgrimage to Tito’s birthplace of Kumrovec with his fellow Pioneers: physically unfit and absent-minded, he often finds himself dropping behind his classmates. He tries to make up for this with unwavering commitment to Tito himself, conjuring him up to appear at opportune moments and direct Zoran back to the righteous path. The apparition of Tito is often shot at a distance, clouded in smoke or backlight, so as to appear all the more mystic and majestic.

When the film finally introduces the ‘real’ Tito in the final scenes (played by Voja Brajović) he is, inevitably, disappointingly small. Vain and slippery, with poorly dyed hair covering up his age, he serves to punctuate Zoran’s arc of self-discovery. Zoran communes with God (a memorable scene in a Church punctuates this) while questioning easily digestible narratives that simplistically answer deeply complicated questions. It’s enough for an eight-year-old, but adults need something more, and Marković’s deft handling of such contradictions through the eyes of Zoran is endearingly funny and heart-warming.

But where does Tito and Me sit amongst other depictions of Tito? Depictions of the man himself were rare: more common was a critique of Titoism, the socialist ideology that had done so much to shape Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav Black Wave – still perhaps the high-water mark of the region’s cinematic tradition – aimed plenty of shots. Želimir Žilnik’s Early Works (1969) took the works of Marx and Engels, held it up to contemporary Yugoslavia and found it wanting; Dušan Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) liberally mixed the sexual revolution, the Leninist Soviet Union and modern Yugoslavia, whilst his earlier film Innocence Unprotected (1968) was another piercing look at male ego in a socialist context. If that all sounds drearily academic, these films are wonderfully anarchic and humorous explorations of such themes. Post-Black Wave, Yugoslavia entered a decidedly more conservative cultural phase. Still, Puriša Djordjević’s Pavle Pavlović (1975) directly criticised the presence of criminality and corruption in the self-managed, worker-owned factories. And a decade later, Emir Kusturica’s Palme D’or winning masterpiece When Father Was Away on Business (1985) would filter the Tito-Stalin split through personal and familial history.

But still, put the man himself on screen? Good luck.

Prior to his 1980, there had been (to my knowledge) only two depictions of Tito in Yugoslav film: Sutjeska in 1973, a big-budget WWII film starring none other than Richard Burton, hand-picked by the Great Leader to play himself. The film was one of a cycle of Partisan war films glorifying the fight against the Nazis: some of them hold up as top-tier blockbuster spectacle but despite the best efforts of Port Talbot’s finest, Sutjeska isn’t one of them. Burton could glower into the middle-distance like few others, but it’s not enough to save a stodgy, heavy-handed film that seems in fear of the responsibility bestowed on it to depict Tito.

The other one depiction of Tito prior to his death – and this is a stretch – is his appearance from archival footage in Lazar Stojanović’s incredible Plastic Jesus (1971). Made as a master’s thesis, Plastic Jesus was a boundary-breaking experiment across narrative fiction, the essay film, and documentary making. Tito’s appearance in archival footage was placed in proximity to archival footage of Hitler, Stalin and Ante Pavelić (Croatia’s Nazi-installed wartime puppet). In doing so, Stojanović was drawing a direct line of parallel between the creation of cults of personality and the film’s chaotic, sleazy protagonist Tom (Tomislav Gotovac). For his troubles, Stojanović was imprisoned albeit not for offending the Man Upstairs, but – technically – for offending the military (a scene in the movie contained documentary footage of military higher-ups inebriated and singing nationalist songs, a big no-no in multiethnic Yugoslavia).

Even as Yugoslavia fell apart, depictions of Tito did not exactly increase in volume. Croatian director Vinko Brešan’s Maršal (1997) tells the story of a Dalmatian village seemingly haunted by Tito’s ghost, with the mayor seeing it as an opportunity to turn island into Yugo-kitsch holiday park. Žilnik’s medium-length Tito for the Second Time Amongst the Serbs (1992) was filmed as the country had fully descended into war. A Tito-lookalike (Dragoljub Ljubičić) walks the streets of Belgrade and chats with passers-by, who treat the lookalike like the real thing. The resulting conversations are electric, an in-the-moment capture of an entire people suddenly losing their belief in God (Tito) and unable to square the cognitive dissonance with their own collapsing reality.

In some ways, the people of Tito for the Second Time… are just grown-up versions of Zoran from Tito and Me, paying – consciously or not – for their steadfast belief in a lone individual at the top of the food chain as opposed to the complex forces of ideology and power that more readily and chaotically shape our world. Perhaps that’s why so few films even now readily and concretely depict Tito (amongst the films in these programme notes, he never appears as a concrete character).

But the character of Tito is arguably uninteresting. More interesting is our relationship to him, our relationship to the authority figure, our collective willingness to absolve ourselves of guilt if only there was someone, anyone, to tell us what to do and how to feel. And Tito and Me stands confidently here, a film depicting precisely what happens when you shake off that childish attachment to authority and stand on your own two feet.

Author Biography: Fedor Tot is a Novi Sad-born film critic and curator specialising in Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav cinema, with bylines at Little White Lies, MUBI Notebook and Screen Slate. He is currently undertaking a PhD with the School of History at University of East Anglia.

This original essay was written for the inaugural first edition of the Serbian Film Festival UK, London 7-9 March 2025.

Liberating Cinema would like to thank Delta Video, Belgrade for providing the film images used in this essay.