Early Forays into the Argentine Modern Short Film

By Leandro Varela

Though the short film form was, until 1950’s Argentina, usually associated to early silent films, newsreels, sponsored films, animated serials and home movies, we do find a series of modern short films or predecessors to the modern short film which precede this decade. These came in the form of noteworthy amateur films, films done by the artist Horacio Coppola, an early foray into film directing by Leopoldo Torre Nilsson and as a series of lauded sponsored documentaries. The modern short film would eventually be extensively developed and brought to the mainstream by the Short Film Generation, a movement which erupted in the early fifties and which would produce new short films at an increasingly rapid rate until the mid 1960’s.

Photographer and Secretary of Cine-Club de Buenos Aires,[1] Horacio Coppola produced a body of work which constitutes “one of the most direct precedents of the modern short film” (Cossalter, 2016, p. 71). After a european trip in which he worked on three experimental short films, Traum (co-directed with Walter Auerbach, 1933), Un Quai de la Seine (1934) and A Sunday in Hampstead Heath (1935), Coppola directed Así nació el obelisco (1936). In this film, which depicts the construction of the iconic Buenos Aires obelisk, we see the use of rhythmic montage and “the presence of a constantly moving and dynamic camerawork” (Cossalter, 2016, p. 71), both of which “would be traits and means which the 1960’s modernity would retake and exploit to its fullest” (Cossalter, 2016, p. 71).

Before becoming internationally recognized for his feature films, Leopoldo Torre Nilsson made a short film in 1947, an “isolated albeit remarkable date within our short film history” (Mahieu, 1961, p. 20). This film is titled El muro and it is based on one of his short stories, El muerto. The film “participated in an avant-garde style wherein we could already, in symbolic form, find a few of his future recurrent themes: individual alienation, loneliness, the subjective vision of the World” (Mahieu, 1961, p. 20) and “presents literary and formal characteristics typically associated to the old avant-garde, but also a personal vision” (Mahieu, 1961, p. 20). After making this film, Torre Nilsson devoted his career to making feature-length films and, though not usually associated to the 60’s Generation movement which would come out of the Short Film Generation, his and Fernando Ayala’s success “was an important stimulus to the development of a cinema that would reject some of their achievements while emulating others” (López, 1988, p. 54).

As far as modern short film productions by amateur filmmakers are concerned, the pre-1950’s films produced within the context of the cine-club Club Cine Argentino are often mentioned. This cine-club began organizing filmmaking contests in 1933 which served as an important stimulus for independent short film production.[2] Despite this incentive, José Agustín Mahieu (1961), author of the 1961 classic Historia del cortometraje argentino, indicates that

the persistence in the canons of amateur cinema and the consequent independence in the face of commercial impositions, did not impede a standstill within conventionality, in the reduced framework of family and touristic cinema, when not in the aging formal experimentations, aggravated for the most part due to content ingenuity and technical poverty. (p. 17)

He highlights however that two films associated with the CCA produced before 1950, Caperucita Roja (Méndez Delfino, 1933) and De un solo tiro (Carlos Duverges, 1937), were presented to international contests and festivals. The former was produced by CCA whereas the latter was produced by a member of CCA and won an award at an unspecified international contest in Paris. Javier Cossalter (2016), author of the doctoral thesis El cortometraje en Argentina y su relación con la modernidad cinematográfica (1950-1976), on the other hand stresses that although there is unfortunately not much information regarding these films or their whereabouts, “avant-garde precedents in the short film” (pp. 71-72) similar to those found in Coppola’s Así nació el obelisco “should be sought after in 16mm amateur fiction and documentary films produced within the CCA in the 30’s and 40’s” (pp. 71-72).[3] A couple of other early shorts produced by CCA include Nahuel Huapi y su región (Emilio Werner, 1937) and Luz y sombra (Enrique de la Cárcova, 1937).

Working in the field of sponsored filmmaking, the Italian director Enrico Gras’ films constituted what Mahieu (1961) calls an exception to “a meager, and always far from any possibility of artistic transcendence, panorama” (p. 18). His 1940 film La ciudad frente al río was a documentary that according to Mahieu “exceeded the limited proposals of diffusion which the Municipality which produced it induced” (p. 18) and is “a clear and didactic model of exposition, which at the same time values the sense the work with imagination and talent in the use of visual metaphors and of a precise and agile ideological montage” (pp. 18-19). Gras would continue making short films in Argentina during the forties and fifties before returning to Italy.

Other sponsored films and documentaries mentioned by Mahieu (1961) as being predecessors to the modern short film include the documentary film productions of the Instituto Cinematográfico Argentino, later known as the Instituto Cinematográfico del Estado: Tigre (1939), Nahuel Huapi (1941), Playa Grande (Amanda Lucía and Héctor Bernabó, 1943), Vendimia [1941/1943] and the CINEPA-produced documentary Los pueblos dormidos [The Sleeping Villages] (Leo Fleider, 1947). Concerning these productions, Mahieu indicates that they are “precursors of a yet unexplored documentary cinema” (p. 18) which are worth remembering. Three of these films, Tigre, Playa Grande and The Sleeping Villages, preserved at the Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken in Buenos Aires, have recently been digitized and made available online.

After its rediscovery by Javier De Azkue and Carolina Cappa, the Museum and Televisión Pública (Argentina’s national public broadcaster) produced a restored digital copy of The Sleeping Villages using three separate copies of the film.[4] This new copy was screened publicly in the University of Buenos Aires on 24th November 2016[5] and released online through the Archivo Histórico Radio y Televisión Argentina’s Youtube channel on 29th December 2016.[6] Copies of Playa grande and Tigre have recently been digitized at the Museum and released online through the Museum’s social media accounts (Youtube and Instagram) on 21st and 27th March 2021, respectively.[7] These releases were carried out within the context of the March 2021 edition of the Museum’s La hora del museo online, an online screening series. This edition of the series was curated by Andrés Levinson and focused on the Cine Escuela Argentino, the cinematographic branch of the Comisión Nacional de Radioenseñanza y Cinematografía Escolar, created by the Secretaría de Educación in 1948.[8] Each entry of this edition’s series, which can still be accessed through the Museum’s Youtube page, includes an introduction by Andrés Levinson, who provides valuable information regarding the production of these films and the context in which they were produced as well as an analysis of these films.

Two State-sponsored films: Playa grande and Tigre

The 69th article of the Law No. 11.723 which regulates intellectual property and was passed by Congress on the 26th of September of 1933, indicated that collected funds would be designated to the encouragement of the arts. In this article’s section g, it is indicated that 20% of said funds will be designated to the creation of the Instituto Cinematográfico Argentino, destined “to promote the national cinematographic art and industry, general education and the country’s propaganda abroad, through the productions of films for the institute and third parties.” This institution was eventually created through the Decree Law No. 88.384 (1936) which established a commission for the organization, regulation and functioning of the ICA. This decree was signed on the 18th of August 1936.[9]

Placed at the helm of this institution were the conservative senator Matías Sánchez Sorondo (as Chairman) and the outspoken film critic Carlos Alberto Pessano (as its Technical Director), who were both behind the film magazine Cinegraf. The Institute was finally regulated by the Decree No. 98.432 signed on the 19th of August 1941. According to this regulation, the institution was to be renamed to the Instituto Cinematográfico del Estado and would have, amongst its various functions, “the production of official films to be carried out by the State Departments or by self-governing entities” (art. 2). The ICE would finally be replaced by the Dirección General de Espectáculos Públicos, created by the Decree No. 18.406 signed on the 31st of December 1943.

Once named as the technical director of the ICA, Pessano resigned from his position as director of Cinegraf to focus his energy at ICA. When directing Cinegraf, he would publish editorials titled Primer plano in which he gave his highly critical and notorious points of view in regards to the current state of affairs of national film production and what could be done to improve it.[10] His ideas on cinema “revolved around three axes: the defence of nationality, the appreciation of highbrow cinema and the rejection of popular cinema and the need to exercise control in the form of censorship for the defence of the spectators” (Kriger, 2010, p. 267). These three axes would “underlie as an ideological framework to the administration which he carried out alongside Sánchez Sorondo in the Institute” (Kriger, 2010, p. 272).[11] Levinson (2021b) suggests that Pessano and Sánchez Sorondo’s ideas on cinema published in Cinegraf also served as an ideological and cinematographic framework which underlies the film production carried out by the Institute during their tenure. He points out the “european-look” of Tigre, noting how the setting and the people in this film have distinct European features (2021b), and both he (2021b) and Kriger (2010) note the focus on young and athletic people and how they interact with the surrounding nature in what seems to be an idyllic setting. These highlighted characteristics could very well be considered as carefully thought out choices guided by Pessano and Sánchez Sorondo’s aforementioned ideological concerns.

Between 1939 and the early forties, Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales, the state owned oil company, commissioned the INC (later the ICE) a series of films which would depict various iconic natural sites from around the country. The INC/ICE thus produced Tigre, Playa Grande, Nahuel Huapi and Vendimia, films which “stood out for their excellent production, with a good use of stylistic and technical means which weren’t very common at the time” (Kriger, 2010, p. 274) and which “despite their touristic characteristics, were endorsed, due to certain conceptual seriousness and a plastic style based on a good technical knowledge of framing and lighting” (Mahieu, 1961, p. 18).

Tigre

Tigre, produced in 1939, is a 12-minute documentary which focuses on the Tigre, a town in the north of the Province of Buenos Aires which lies on the Paraná Delta. The photography for this film was done by Fulvio Testi, H. Chiesa and Pabo Tabernero and the music was done by Spanish-born Alejandro Gutiérrez del Barrio and the editing by H. Proserpio. The director of this work is not credited.

After its opening titles, Tigre begins with a three-minute sequence in which, in typical sponsored documentary fashion, a narrator describes and promotes the town of Tigre whilst his words are illustrated by a series of shots of maps and views of the town. A geographic description is followed by descriptions of the views and leisurely activities typically carried out there, such as rowing or sailing. The narrator then provides a brief overview of the local industries such as fruit harvesting, forestry and paper manufacturing. He finally indicates that it is in this place that the images we are about to see were filmed, and proceeds to announce: “the sun rises in Tigre” (INC, 1939, 02:45). The rest of the film contains no text or dialogues, only images which are accompanied by Gutiérrez del Barrio’s music.

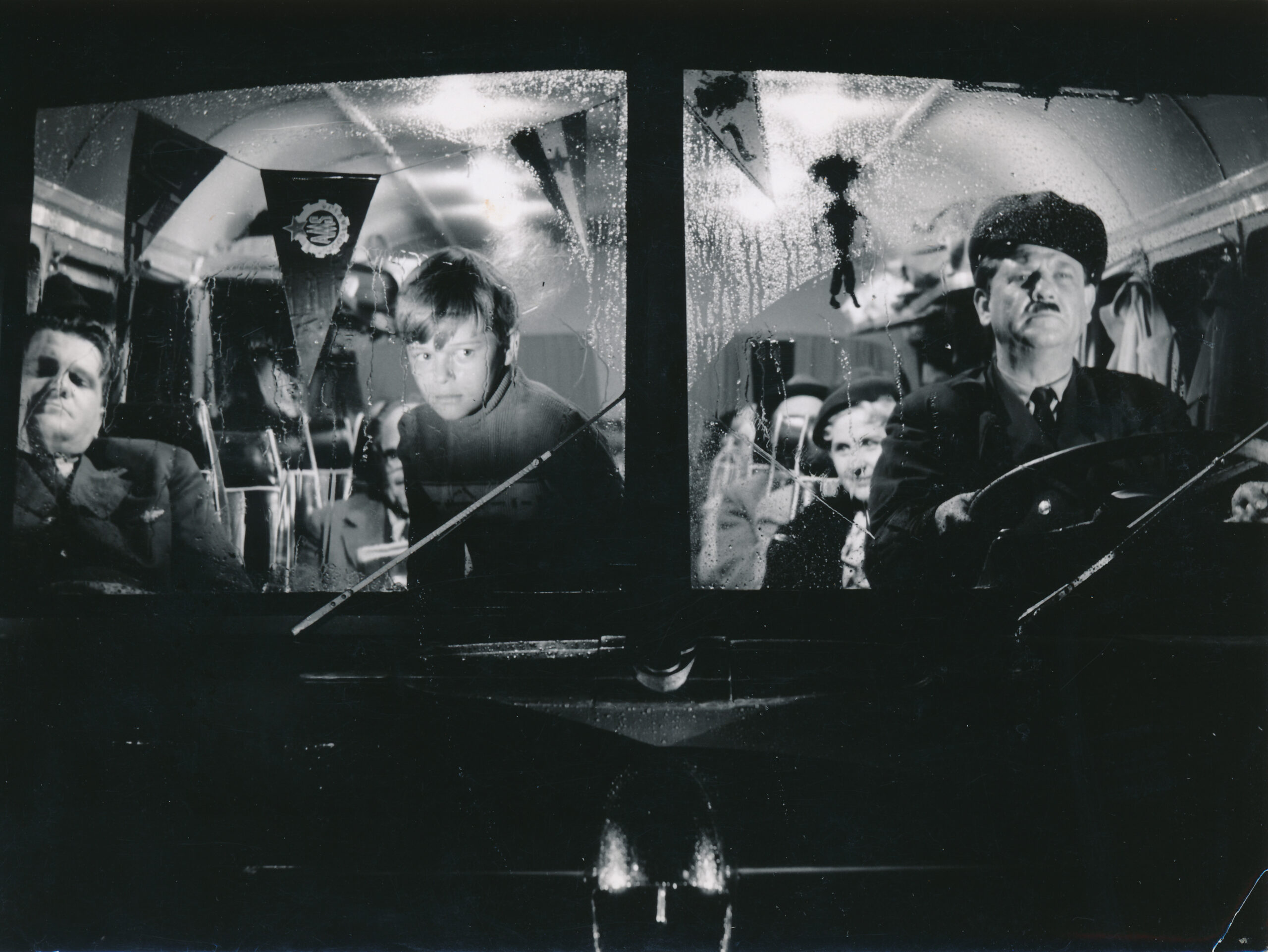

The second part of the film begins with a series of shots of Tigre’s canals at dusk. We then see a series of young people, couples and families carrying out a series of leisurely activities: rowing, sailing, diving, swimming, going to the park, fishing, grabbing flowers, having picnics and barbecues. These shots are intertwined with shots of the scenery, close up shots of flowers, fruits, pets and of young women. By the end of this sequence, we see a series of shots in which various women lie down either at a park, boat or hammock for a nap, and this sets off what seems to be a very short dream sequence: A shot of a woman laying down and closing her eyes is followed by two shots of sceneries in which we see a series of trees, houses and boats on the border of canals and their reflection in the water, one seemingly abstract shot of trees behind the setting sun, and another semi-abstract shot of the moving reflections of masts on the water (fig. 1). The shots of this sequence, which ends with a transition and a change in the music’s tempo, were edited in such a way that they contain very slow cross-dissolves in between them. The film ends with the motorboating sequence. A motorboat wakes up the people taking a nap and a young couple go for a motorboat ride through the canals of Tigre (fig. 2). They appreciate the scenery and greet their neighbours who also went out for a ride in the canals. Some are sailing, others are waterskiing and others are rowing. As the sun sets, the music changes tempo and we see shots of the couple, possibly returning home, a travelling shot through a canal, rowers, and a couple of sceneries before the film ends with a close-up shot of the water.

Tigre, which was widely distributed and screened alongside feature films in important film theaters, was described by critics at the time as (La Nacion, as cited in Kriger, 2010) “expertly edited, with a speed and power of synthesis which the technically familiarized will appreciate through its enunciation” (p. 274) who noted that it “conciles the informative mission with the aesthetic preoccupation, reflected in the precious and poetic graphical language, a photography of plastical merits […] and the balanced coordination of its elements of beauty” (p. 274). Levinson (2021b) indicates that certain characteristics of this film, such as the absence of a narration (limited to the three-minute prologue) and a reliance on photography and editing without a voiceover, approach this film to the avant-garde tradition.

Playa grande

Playa grande is a 1943 12-minute documentary whose focus is Playa Grande, one of the main beaches in the city of Mar del Plata. It was directed by Amanda Lucia Turquetto (credited as Amanda Lucía, she was also the editor, alongside Enrique Alcoy) and Hector Bernabó (also the screenwriter, alongside Roberto Moro). The photography was done by Swiss photographer Francis Böeniger and by S. Wehner and the music by the aforementioned Alejandro Gutiérrez del Barrio. Not much is known about the directors, Amanda Lucía Turquetto or Héctor Bernabó. Amanda Lucía Turquetto was apparently associated with the concretismo art movement of the 40’s and supposedly did graphic design for a magazine produced by one of the concretismo groups. Levinson (2021a) hypothesizes that the co-director credited as Hector Bernabó is in fact the argentine-brazilian artist Carybé (née Héctor Bernabó), who was in Argentina during the early forties. Levinson (2021a) also points out that this possible association the two directors had with the arts explains the noticeable plastic qualities of the film.

This film contains no narration in its soundtrack and, besides the credits, as well as an opening and a closing intertitle, no text. The first intertitle simply indicates that the film was filmed during the summer of 1943 and briefly describes the characteristics of this traditional argentine beach. The final intertitle states that the ICE works to show the country to argentines so as to further their knowledge of their fatherland and to show foreigners a few aspects “of a great ongoing Nation” (Lucía, A. & Bernabó, H., 1943, 12:20-12:35). Less evidently structured than Tigre, Playa grande begins, before the opening credits, with a mysterious close-up shot of an unnamed woman at an unidentifiable location who opens her eyes, stares at the camera and smiles (fig. 3). The film then begins showing a series shots of the waves of the Atlantic Sea at dusk. We then see shots of waves breaking on the shores of Playa Grande and then some shots of an empty seaside resort and a worker setting it up for the arrival of the bathers. We then begin to see people arriving at the resort, such as young women and young families who proceed to carry out a series of activities at the beach: sunbathe, walk on the shore of the beach, run, surf and row. We also see shots of children playing and mothers looking after them. These shots are intertwined with aerial shots of the crowded resort (fig. 4), shots of the waves, waves breaking on the shores and close up shots of young women. This sequence ends with the close up shot of a woman laying down on the sand and with a change of tempo in the soundtrack’s music. We then see a somewhat disconcerting close up shot of the hand of another woman (as we come to realize from the shot that follows it) who grabs some sand. A close up shot of a woman, possibly the same one who stares at the camera at the beginning of the film, is followed by a series of shots of waves breaking on the shores and some close-up shots of sea foam. The focus is then shifted from the seaside resort to some dunes and an empty beach. We see shots of the sky, the dunes, ruins, a series of young women climbing up the dunes and going down them to arrive at an idyllic empty beach (fig. 5). The film finishes with a workers’ sequence: We see artisans weaving baskets, and, as the sun sets, fishermen getting ready to set sail on their ship. As the night approaches, we see a few more shots of the waves and the shoreline. The film ends with a shot of sand on which the closing intertitles are printed.

Levinson (2021a) indicates that various characteristics of this film approach it to the avant-garde tradition. He indicates that the opening sequence in which the beach “wakes up” remits to sequences in Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) in which the cities and rural areas wake up. He also refers to the abstract shots of the waves breaking on the shores of the beach as well as the close up shots of the sea foam, reminiscent of H2O (Ralph Steiner, 1929). He also indicates that the close up shots of the young woman can be associated with the portraits which German-born photographer Annemarie Heinrich would shoot in that period. He states that the overall characteristics of the film, which include a fascination for the water, dunes and waves portrayed in well thought compositions remit the film to this tradition.

The Sleeping Villages

The short documentary film The Sleeping Villages, which centers around the life of the people living in the Quebrada de Humahuaca in the province of Jujuy, was produced by CINEPA, a distribution and production company founded in 1947 which would produce animated short films, educational documentaries, re-distribute short films produced abroad and sell 16mm “Cinepavision” branded projectors for home use.[12] CINEPA would for example produce the Burone Burché animated series El Refrán animado, Jorge Caro´s Plácido series, distribute new versions of films by animator Juan Oliva such as La caza del puma (1940) and redistribute a series of Castle Film productions.[13]

In the late forties and early fifties, possibly seeking to benefit from the new mandatory newsreel and documentary short film screening legislation, the 20.993 Decree signed on the 7th of September 1946, CINEPA began producing a series of documentaries about different regions of the country: films were shot in the jesuitic ruins of San Ignacio in the Province of Misiones, in the city of Buenos Aires, in the Quebrada de Humahuaca and elsewhere. This decree was a response to the aforementioned Decree No. 18.406 (1943) which indicated the DGEP would have to “stimulate the production of newsreels and documentary films of national interest” (art. 7, sect. b) as one of its functions. According to the second article of the new Decree No. 20.993 (1946), although the screening of newsreels and/or documentaries was mandatory, film theaters could choose which newsreel or documentary they would screen, so long as these films had been authorized by the DGEP and produced by a company which was also authorized by this agency. Though this film is not a sponsored film in the strict sense of the term, having been authorized for screening by the DGEP, The Sleeping Villages benefited greatly from this legislation as it helped to set the conditions for its widespread distribution.[14]

The Sleeping Villages is a 22-minute documentary from 1947 about the life of the people living in the villages along the Quebrada de Humacuaca mountain valley. The film was directed by Polish-born Leo Fleider, produced by Pedro López, with a script by Francisco Madrid and music by Sergio Villar and Justiniano Torres Aparicio.[15] The film’s photography was done by Hugo Chiesa[16], the sound by Ortiz de Guinea and Mario Fezia, editing by Estudios A.J.R. and the narration was done by Pedro Del Campo. The director Leo Fleider would go on to have a successful career as a feature filmmaker.

Through the use of narration and images which illustrate the narrated text, a very brief history of the Quebrada de Humahuaca is provided and the local customs, rites and everyday life are described. The impact and benefits brought on to the villages by the State and the Church are also highlighted in the narration. The text revolves around the theme of the “sleeping villages” which lie across the Humahuaca Mountain Valley, a place where supposedly time stands still and where “what happens in one day is the same as what happens in a year…and in one hundred” (Fleider, 1947, 04:20-04:30). Four main sequences were identified: the opening sequence, in which the history of the Quebrada is narrated, the main sequence in which everyday life, local customs and rites and the impact of the Church and the State in the local tradition are described, the carnaval sequence, in which we are presented with a representation of the carnaval, and the final funeral sequence in which the funeral of a young boy is narrated.

In an interview with Pamela Vázquez (2017) of the Museo del Cine, researcher Radek Sánchez Patzy states that he found that this film seems to have not been premiered in Jujuy and that it was apparently directed towards a metropolitan audience to whom the producers had the intent to “approach them an experience of cultural otherness” (para. 4). He also notes that the notion of the villages in the Quebrada de Humahuaca being “sleepy” did not reflect the reality at the time. Regarding documentary films depicting life in Jujuy in the late forties such as The sleeping villages and En las tierras del silencio (Héctor Peirano, 1949) he indicates in the interview (Vázquez, 2017) that:

various metaphors to describe the quebradeña and puneña societies, characteristic of the time in which they were produced, are omnipresent, abounding in a narrative which thinks these human spaces as being silent, docile, sleepy, quiet, ahistoric, even when their own records show exactly the opposite (para. 6).

Though he considers it a precursor to the modern documentary, Mahieu (1961, p. 18) also defines this film as an “ambitious attempt of a documentary directed by Leo Fleider in the argentine North, which doesn’t make the most out of its material and contains a very conventional script”. Though this documentary is indeed much more conventional than Tigre and Playa Grande and harder to approach it to the avant-garde, we do find a series of modernist gestures in it. Though we won’t define what constitutes a modern film,[17] we will indicate a few of these gestures which we found: In the main sequence, we are shown how, after getting married at a Church, the local custom was for the couple to go to their house and have a traditional wedding ritual carried out by the Godfather. The final shot showing this ritual fades to black and, after a few seconds of a black screen, a shot of the local skyline fades-in. It’s in this moment that the narrator indicates that the ritual is followed by “an intimate, almost mysterious, feast, which no external eye can see” (Fleider, 1947, 08:50-08:55) and proceeds to mention that nuptial music would be played. His speech is followed by the sound of the aforementioned music whereas the shot of the scenery is followed, through a cross dissolve, by a shot of the sky. The sequence of shots which anticipate and accompany this text: a black screen, a shot of the skyline and an abstract shot of clouds, could very well represent the subjective point of view of the narrator who, unable to illustrate the feast which he isn’t allowed to see, resorts to fill this portion of the narration with abstract imagery.

In the final sequence of the film, we find two men praying for the life of a young boy. The action begins with a series of close-up shots of various details outside and inside of a church, including a shot of its ringing bells and of a hanging crucifix. A shot of the two men praying (fig. 6) is followed by a countershot of the crucifix, which is followed by the countershot of the two men praying and ends with a close-up shot of the crucifix, which begins to move as if anticipating a miracle (fig. 7). We find out in the following shots and narrated text that the young boy passed away, as we see his funeral ceremony carried out. The peculiar shot of the moving crucifix, which seems to disregard the conventional rules of sponsored documentary films at the time, could very well be a subjective vision of one (or both) of the two men praying, a modernist trait.

[1] For more information regarding the early history of Argentine cine-clubs, see Couselo (1991).

[2] A total of 550 films participated in the 56 filmmaking contests organized by CCA between 1933 and 1957 (Mahieu, 1961, pp. 16-17).

[3] It’s interesting to note that in a 1956 screening series dedicated to argentine documentary and experimental films organized by Cine Club Núcleo, films by two amateurs from CCA were screened alongside Tigre (1939), La flecha y un compás (David José Kohon, 1950), The Sleeping Villages (Leo Fleider, 1947), El muro, Turay el enigma de las llanuras (Enrico Gras, 1950), Los últimos nueve minutos (José Ingenieros), Despertar (Guillermo Maceira) and Rapsodia en abstracto (Alfredo Rubio).

[4] This new copy was made from two incomplete nitrate copies and a complete 16mm copy. One of the incomplete nitrate copies used for this restoration contains the English version of the film.

[5] The film was presented by Carolina Cappa and researcher Radek Sánchez Patzy at the Jujuy en el cine. 1930-1970 imágenes y sonidos inéditos screening exhibition. It was presented alongside the films En las tierras del silencio (Héctor Peirano, 1949) and Defensa del Pucará (1958). This exhibition was later presented, on the 19th of april, 2017, in the city of Tilcara, Province of Jujuy, in an event organized by the Centro Universitario Tilcara.

[6] See the Archivo Histórico RTA YouTube page (https://www.youtube.com/c/ArchivoHist%C3%B3ricoRTA). The film was also uploaded to the Museum’s YouTube page on the 22nd of August 2017: See the Museo del Cine “Pablo Ducrós Hicken” YouTube page (https://www.youtube.com/c/MuseodelCinePabloDucrósHickenBuenosAires/).

[7] See the Museo del Cine “Pablo Ducrós Hicken” YouTube page (https://www.youtube.com/c/MuseodelCinePabloDucrósHickenBuenosAires/) and the Museo del Cine Instagram page (https://www.instagram.com/museodelcineba/). The Museum also has a Facebook page: see Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducrós Hicken (https://www.facebook.com/MuseoDelCineBA).

[8] For more information on this edition of the screening series, see Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken (2021).

[9] This was a rather strange moment to pass such legislation, especially considering the increasingly thriving national film industry and a situation in which state protection for the film industry seemed unnecessary.

[10] For an analysis of Pessano’s writings published in Cinegraf, see Spadaccini (2012).

[11] For an analysis of Sánchez Sorondo and Pessano’s administration of the ICA and ICE, see Kriger (2010).

[12] For more about CINEPA and its collection preserved at the Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken, see Ugalde (2021).

[13] For more on the life and work of Burone Burché, Jorge Caro and Juan Oliva, see Manrupe (2014, pp. 30-37).

[14] Sánchez Patzy hypothesizes (Vázquez, 2017) that the producers at CINEPA might’ve chosen to make this film in order to capitalize the recent public interest in the indigenous issues of the Argentine Northwest which arose following the 1946 Malón de la Paz march, a march wherein indigenous peoples from this region marched to Buenos Aires to claim the restitution for their ancient lands.

[15] Jutiniano Torres Aparicio “surely the most important jujeño musician of the 20th Century”, as indicated by Sánchez Patzy (Vázquez, 2017, para. 4) musicalized the carnival sequence with his song La vi por vez primera which was premiered in this occasion.

[16] Possibly the same director of photography for Tigre, credited in that production as H. Chiesa.

[17] See Cossalter (2016).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

References

Archivo Histórico RTA. (n.d.). Home [YouTube page]. YouTube. Retrieved June 14, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/c/ArchivoHist%C3%B3ricoRTA

Jorge Miguel Couselo. (1991). Los orígenes del cineclubismo en la Argentina y “la Gaceta Literaria”. In Actas del III Congreso de la A.E.H.C. (pp. 435-439).

Javier Cossalter. (2016). El cortometraje en la Argentina y su relación con la modernidad cinematográfica (1950-1976) [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de Buenos Aires]. Repositorio Filo. http://repositorio.filo.uba.ar/handle/filodigital/4616

Decreto Ley No. 88.384 (1936)

Decreto No. 18.406 (1943)

Decreto No. 20.993 (1945)

Decreto No. 98.432 (1941)

Leo Fleider. (1947). Los pueblos dormidos [The Sleeping Villages] [Film]. CINEPA.

Alejandro Gutiérrez del Barrio (Music). (1939). Tigre [Film]. Instituto Cinematográfico Argentino.

Clara Kriger. (2010). Gestión estatal en el ámbito de la cinematografía argentina (1933-1943). Anuario del Centro de Estudios Históricos “Prof. Carlos S. A. Segreti”, 10(10), 261-281. https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/anuarioceh/article/view/23158/22894

Andrés Levinson. [Museo del Cine “Pablo Ducrós Hicken”]. (2021a, March 21). La hora del Museo: Playa Grande (1943) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBIVgHNVXsY

Andrés Levinson. [Museo del Cine “Pablo Ducrós Hicken”]. (2021b, March 27). La hora del Museo: Tigre (1939, Carlos Alberto Pessano) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubFSfeeH3Nw

Ana Lopez. (1988). Argentina, 1955-1976: The Film Industry and its Margins in John King and Nissa Torrents (Eds.), The Garden of Forking Paths: Argentine Cinema (pp. 49-64). BFI.

Amanda Lucía & Héctor Bernabó. (1943). Playa Grande [Film]. Instituto Cinematográfico del Estado.

Agustín Mahieu. (1961). Historia del cortometraje argentino. Instituto de Cinematografía de la Universidad del Litoral.

Raúl Manrupe. (2004). Breve historia del dibujo animado en la Argentina. Libros del Rojas.

Ley No. 11.723 (1933)

Museo del Cine. (n.d). [Instagram page]. Instagram. Retrieved June 14, 2021, from https://www.instagram.com/museodelcineba/

Museo del Cine “Pablo Ducrós Hicken”. (n.d.). Home [YouTube page]. YouTube. Retrieved June 14, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/c/MuseodelCinePabloDucrósHickenBuenosAires/

Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducrós Hicken. (n.d.). Home [Facebook page]. Facebook. Retrieved June 14, 2021, from https://www.facebook.com/MuseoDelCineBA

Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken. (2021). La hora del Museo online: Colección Cine Escuela Argentino. https://www.buenosaires.gob.ar/noticias/la-hora-del-museo-online-coleccion-cine-escuela-argentina

Silvana Spadaccini. (2012). Carlos Alberto Pessano: de la opinión a la gestión. Imagofagia, 5. http://www.asaeca.org/imagofagia/index.php/imagofagia/article/view/251/219

Noelia Ugalde. (2011, February 28). Colección Cinepa. Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken. https://museodelcinebaires.wordpress.com/2011/02/28/coleccion-cinepa/

Pamela Vázquez. (2017, August). El sueño de los despiertos. Asociación de Amigos del Museo del Cine. https://museodelcineba.org/blog/el-sueno-de-los-despiertos/

Author Biography: Leandro Varela is an Audiovisual Archivist at Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken, Buenos Aires. An archivist, curator, and experimental filmmaker, he completed his degrees in Film Studies at Roma Tre University, and Archival and Library Science at La Sapienza University, and attended multiple FIAF Training Programmes. He is a member of RAPA (Red Argentina de Preservadores Audiovisuales), AREA (Asociación de Realizadores Experimentales Audiovisuales) and the newly founded AMANEA (Archivo de la Memoria Audiovisual del Nordeste Argentino).

This original feature article was written for Argentinian Short Film Movement 1943-1963, Liberating Cinema Film Series 2021.