A Masterpiece of Surrealist Subjectivity and Silence: Diamonds of the Night

By Dina Iordanova

Two boys dressed in rags – but still in sturdy shoes – and wearing absurd-looking long coats with large KL written on the back (the sign of Nazi concentration camps) have jumped from a moving train. They are running for their lives. For the duration of the film, the viewers will be following their desperate escape. The plot is simple – they run, they try to hide but hunger and thirst overpower them, they ask for food, they are reported on, they are hunted down and captured, they are kept in captivity, and then they are killed. Or not. The ending remains unresolved, and indeed it is not the most important thing in this film, which counts at 63 minutes running time.

What is important for this unique masterpiece of cinema is the way in which subjective experiences of time, anxiety, hunger, thirst, longing, and fear are represented with the means of cinema. What is unique is the use of elements of the language of surrealism to make a Holocaust film, one that reveals callous cruelty.

Démanty noci/Diamonds of the Night will remain forever in the history of cinema for its unique usage of surrealist imagery alongside a Holocaust narrative – even though the K-camp escape setting is a context for this profoundly existential film about survival. The ants that crawl in the palm of the protagonist, the close ups, the water running down, the use of symbolic imagery out of context — and the stillness that comes with them – is all directed to depict alienation from a body that is one’s own and yet that refuses to obey.

A long opening shot establishes the characters, running through rugged fields. In many of the scenes we see both protagonists, but in fact it is mainly the subjectivity of one of them, a character connoted here as

The First Boy that provides the backbone of the laconic narrative. It is his dreams, his anxiety, his feelings that are communicated through the switching between the objective representation of the flight and the subjective visualisations of feelings and daydreaming. His budding sexuality is also present. He is aroused, a feeling strengthened by the presence of hunger, by the sight of the young peasant woman in the house where he has risked coming in, looking for food. He is after the bread that she cuts for him but in fact it is sexual attraction. All these still women looking at him from the windows in the silent city that he sees in his daydreaming. It is delirious.

* * *

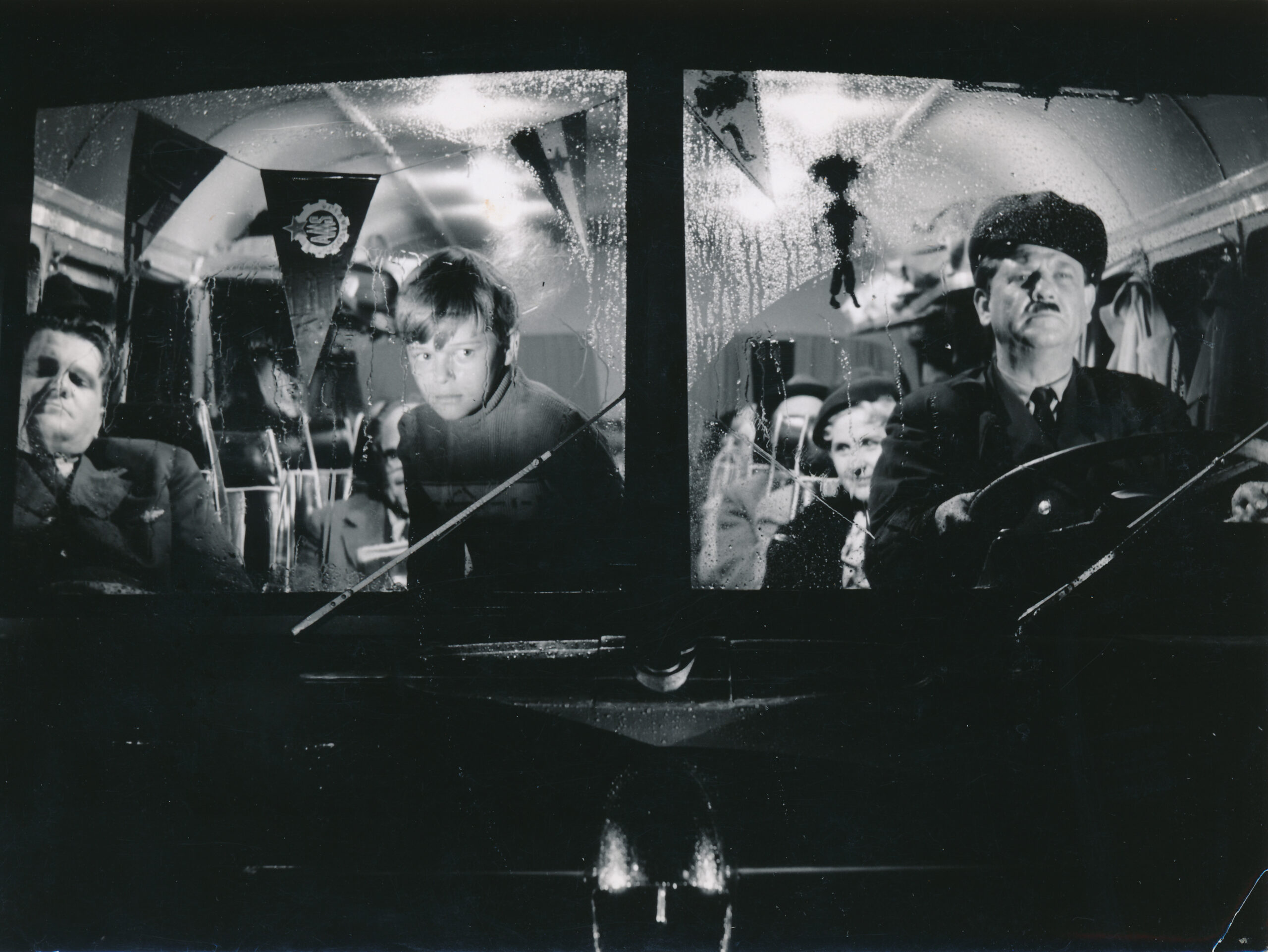

One of the most amazing aspects of this film is the soundscape in which the characters move. The sound is entirely diegetic; the audience only hears sounds the source of which can be immediately identified on screen. The most important is the silence which comes along with the subjective visions that one of the characters experiences. All the scenes of a happy escape, of running behind a tram and getting on it, and the amused passengers onlooking, women in the windows, the protagonist seeing himself happily returning – this all evolves in complete silence, a signifier that this is the inner row of images for the protagonist, the content of his mind. Outside, the noises heard are the noises of the forest or the noise of falling rain, or of running through stones. There are the noises of the hunting party that are coming for them, and then the noises of their drunk singing at the beer celebration after the hunt, when the boys are captive in the corner of the local school gym. Sound does as much as any other of the means of cinematic language used here.

In the overall context of this use of sound, it is a logical consequence that the dialogue is minuscule – and this is what makes the film possible to view even without subtitles. The few spoken exchanges are concerned with the practicalities of expressing hunger, asking for food, or inquiring about the transfer of the prisoners – even if the details of what is said remain unclear, all is clear from the context. The near absence of dialogue only makes the exchanges between captives and captors, between ‘us’ and ‘them’ more intense. Indeed, in his perceptive article on the film, Dominic O’Key zooms in on the mouth, a key surrealistic trope, and its multiple subtle connotations to the specific representation of thirst and hunger in the film, with the intensifying flashbacks to what he terms ‘living hunger’ (111). The camera may frequently focus on the actions of the mouth, yet whilst the boys may be shown devouring mouthfuls of whatever may come their way, in desperation, they are actually ‘eaten alive’ by their captors, the members of the exultant — beer-drinking/sausage-nibbling — local hunting squad.

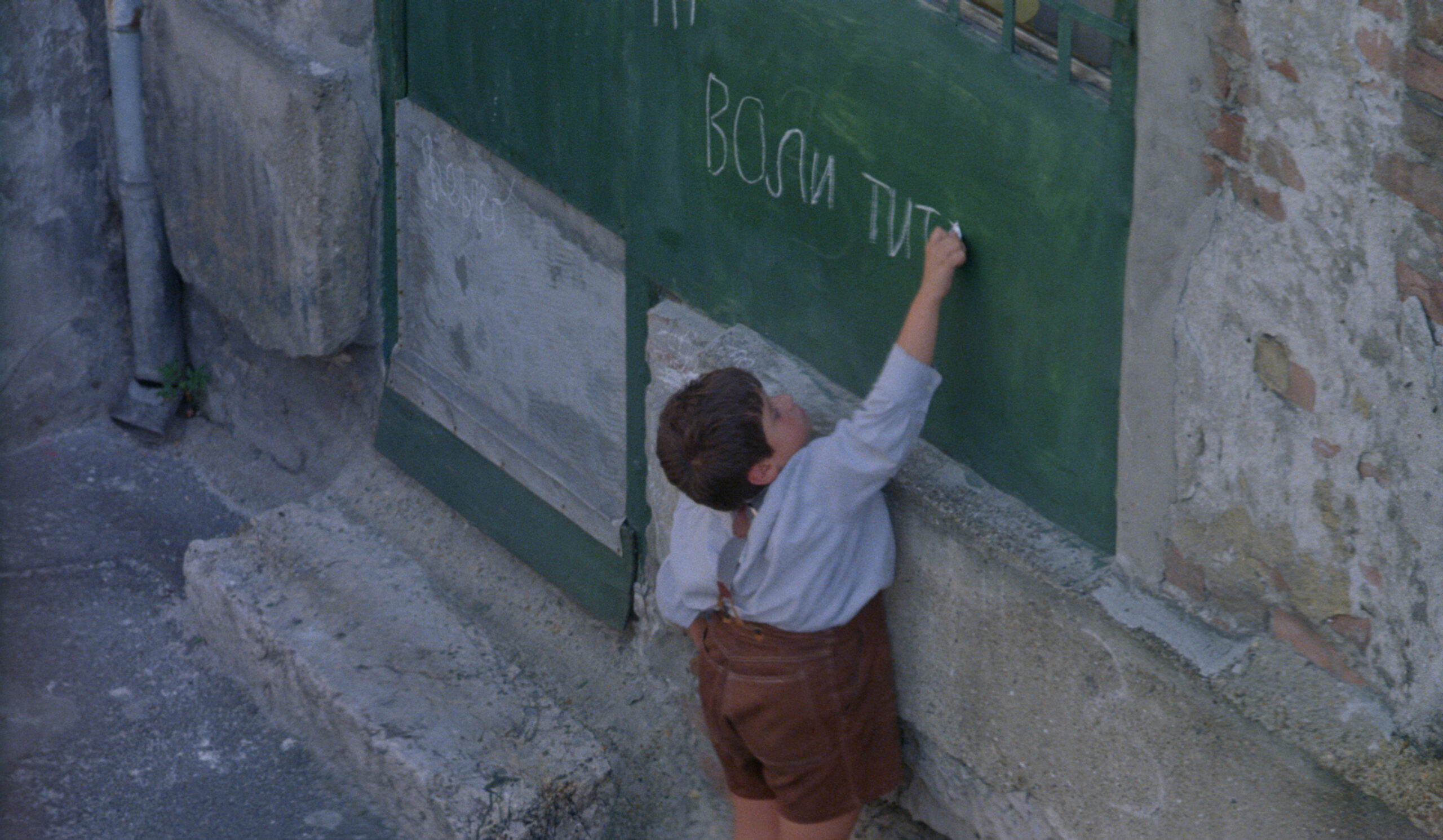

The woman who betrays them may be Czech but the men who hunt the boys are Sudeten Germans; they speak in Deutsch and their allegiances to the Führer are more than clear. They are volunteer paramilitaries, part of the Heimatschutz brigades. It may not necessarily be about anti-Semitism; it is about a deeply divided country. After all, the film is based on the memoir of Czech Jewish author Arnost Lustig, himself a camp survivor: it is he who is the First Boy whose inner monologue is presented.

* * *

There was a significant surrealist tradition already in existence in these lands, since the 1930s, before the arrival of the Czechoslovak directors of the New Wave in the early 1960s. But it is these new filmmakers who take the surrealist thematic and imagery up and transfer them into cinema – people like Jan Švankmajer (A Game with Stones, 1965), Juraj Herz (Cremator, 1969), and Juraj Jakubisko (Deserters and Pilgrims, 1969).

The most distinguished among this surrealist branch of the Czech new Wave, however, is director Jan Němec (1936-2016) who has to his name the three single most important surrealist films of the twenty or so works that would qualify for this label – Diamonds of the Night (1964), Report on the Party and the Guests (1966), and Martyrs of Love (1967). These films are surrealist in narrative, protagonists, set design, costumes, dialogue, and sound; only Diamonds of the Night is an adaptation dealing with historical realities.

It is no longer in line with the standards of present-day film historiography, however, to attribute it all to Němec’s surrealist vision, especially as there is not much surrealism in his later work (and a film he made in the 1970s in exile in Germany, whilst attempting to be surrealist, is only a feeble attempt at that). So, I have wondered if it is not actually a case of ‘one train may be hiding another’, to use Thomas Elsaesser’s term : Namely, it may well be that here, as in so many other instances, it is Němec’s partner, Ester Krumbachová (1923-1996), who is behind the style of a film to a larger degree than previously acknowledged. Between the two of them, she seems to be the true surrealist, from start to finish. At the time of Diamonds’ making, she collaborated on the costumes for Diamonds, eventually writing the scripts and arranging the look for both Report on the Party and the Guests and Martyrs of Love. Unlike Němec, who was surrealist only for the period of their married life, she never stopped being one. Her list of further surrealist credentials is impressive – it includes, among others, the screenplays and costume designs for such surrealist films as Věra Chytilová’s Daisies (1966) and Fruit of Paradise (1970), the script and the sets for Jaromil Jireš’s Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970) as well as for Karel Kachyňa’s The Ear (1970/1990). It seems, therefore, that the Němec/Krumbachová collaboration may be yet one more instance – out of so many in the history of cinema – where the contribution of a female life partner remains in the shadow of a male ‘auteur’, a construct of the way film criticism and cinematic canons work.

The 1968 events in Prague led Němec to emigrate but not immediately, as he only left the country for good in 1974. Of the next twenty-five years, he spent twelve years in the United States and the rest split between Germany, France, and the Netherlands. Even though he had been engaged in some film projects sporadically, his cinematic creativity substantially suffered during this period. He spoke about the impossibility to adjust to America after emigrating in the documentary Velvet Hangover (Robert Buchar and David Smith, USA, 2000). Unlike Miloš Forman and Ivan Passer who stayed in the USA, Němec rushed to go back to Czechoslovakia soon after the end of communism. He lived and worked in Prague until his death in 2014 at the age of 79. Krumbachová never left and passed away in 1996.

Author Biography: Dina Iordanova is Emeritus Professor of Film Studies at the University of St Andrews. She is the founder of the Centre for Film Studies and the publishing house St Andrews Film Studies. An acclaimed academic, prolific writer, public speaker, entrepreneur, and manager, Dina specialises in Balkan, Central, and Eastern European cinemas.

This original essay was written for The Holocaust in the Czechoslovak New Wave Workshop.