Power, Manipulation and Unmasking: Judit Ember and Gyula Gazdag’s A határozat (The Resolution, 1972)

By Pál Czirják

Judit Ember and Gyula Gazdag belong to that select group of Hungarian directors with the largest number of banned films. Although during the Kádár regime the censors in Hungary attempted to avoid the final resort of imposing a total ban on films, instead ordering the reediting of work and even additional shoots, these two artists approached sensitive topics on more than one occasion or expressed such radical criticism that the censors felt they had no other option than to seal certain films by the directors in the cans for many years, or even decades. This is particularly true of their joint, career-launching work, A határozat (The Resolution, 1972), which, by openly revealing the absence of democracy, violated one of the strictest taboos of the then political system.

To gain a better understanding of the political context, it is necessary to examine the historical background. In order to cement the position of János Kádár who rose to power after the crushing of the 1956 Revolution, on the one hand opponents of the system were dealt with in a ruthless fashion, and on the other hand he launched consolidation and made an attempt to build up a new supporter base involving a wide swathe of the general public. This latter policy was achieved by the early 1960s through the introduction of welfare measures and a continued, cautious cultural and economic opening.

From the second half of the 1950s, the cultural policy leadership promoted the emergence of a new circle of artists and intellectuals, who were initially loyal to the system, by launching various forums. During these years, several literary and film journals were established; this is also when the Balázs Béla Studio, which brought together many career-starter filmmakers, came into being. It assisted young artists fresh out of the College of Film to prepare their first projects. In the meantime, it was possible to learn about the most important international intellectual trends (which at the same time meant the influx of Western influences); and albeit only to a limited extent, but over time some space was allowed for the voicing of criticism – naturally, only in the spirit of ‘repairing the mistakes of the system’.

In the economic area, there were moves to relax the rigid planned economy system and, not independently of parallel processes ongoing in Czechoslovakia, experiments were pursued at shaping a more adaptable structure and management better adjusting to real market conditions. The reform wing of the state party, the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party, gained in influence. It aimed at gradual decentralization, that is, the cautious sharing out of certain decision-making powers. The optimistic atmosphere of the 1960s and a belief in the reformable nature of the system were then broken by the crushing of the Prague Spring in 1968. In Hungary, this resulted in stagnation and political regression. Thus, from the 1970s, a period of general disillusionment and stagnancy set in.

Whereas the college days of Judit Ember and Gyula Gazdag were spent in the heady atmosphere of optimism of the 1960s outlined above, their joint, full-length documentary captured this return of the old order by the turn of the decade. What’s more, they achieved this in such an accurate and in so blatant a way that censorship, which in the meantime had hardened once again, simply could not tolerate it.

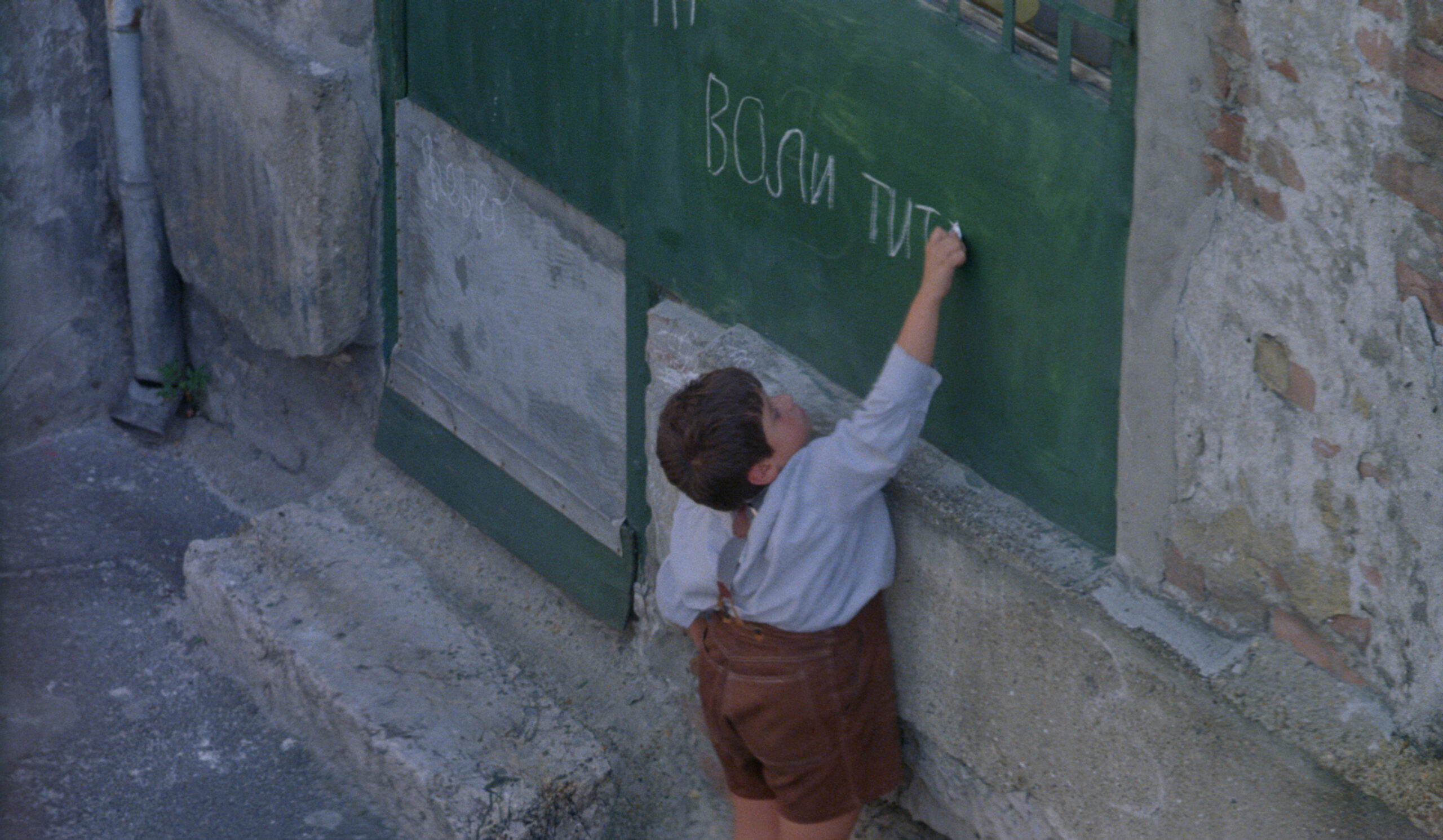

The film The Resolution documents the removal of the head of a rural cooperative initiated and directed by local party functionaries. When given the opportunity, the cooperative membership stood by the doomed president of the association because it was precisely this person who had saved the cooperative from impending bankruptcy, and made it profitable, but local representatives of the party, citing various legal and moral reasons, forced through the ousting of the manager with the membership of the cooperative being placed under intense pressure and intimidation. And all this happened in a legal environment that, in principle at least, guaranteed the autonomy and self-determination of producer cooperatives. The persistent, objective and detailed recording of this lengthy process perfectly demonstrates the fundamental lack of democracy. It focuses the viewer’s attention on the systemic contradictions and although it could not provide insight into the highest circles of political power, it outlines the operation of the entire structure with equal precision on a smaller, local scale.

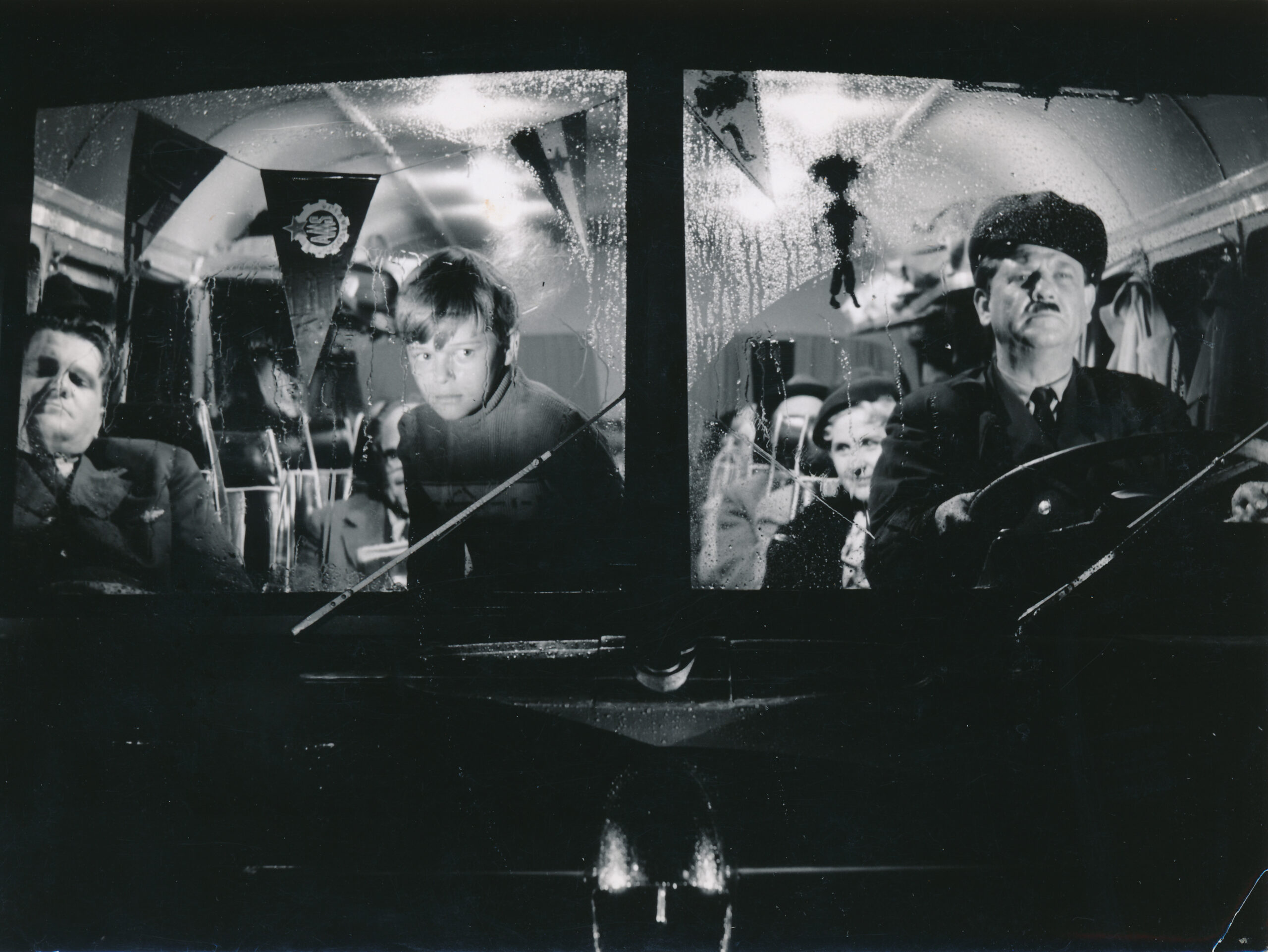

The advantage of the creative methodology, that is, the observer, follower-of-events documentary filming method recording in minute detail key moments but with as little interference as possible, even to the point of avoiding interviews, lies in the fact that it makes evident, in a way that is akin to an imprint, and thus analysable, the internal correlations of the contemporary, but at the same time temporally wider social phenomena. The behaviour of the local party functionaries, their conduct and ways of speaking, the rhetorical and non-verbal gestures of the participants in the course of the film are most revealing in a narrative based on long takes composed around faces. The position as observer shows up an even sharper divide between words and deeds through a lens that scrutinizes the characters persistently, almost impassively.

But if the ‘unmasking’ nature of the documented series of events was so obvious, if the contradiction between the proclaimed ideology and everyday practice was so evident, then how could this project of Judit Ember and Gyula Gazdag ever have been sanctioned? There are at least two answers to this question.

On the one hand, the intention of the culture policy leadership was that this story would not result in the unmasking of the abuse of power perpetrated by the local party apparatus, but instead the ‘immoral’ head of the cooperative who had ‘gone astray’. In their original reading, the film would have been a parable about the exemplary functioning of cooperative democracy at work, in which the membership of the cooperative, exercising their right to self-determination, would rid themselves of a president who had become unworthy of the position. Let us not forget that at the time the documentary was made we were in the years of political regression, of disengagement, when the withdrawal or refocusing of rights shared in the earlier reform period was on the agenda, while at the level of official propaganda, of course, every effort was being made to maintain the illusion of self-governance. Even though the actual events surrounding the removal of the cooperative chief turned out differently from what the political decision-makers would have expected, since the work was done in the Balázs Béla Studio (which from its foundation had been exempted from the so-called ‘presentation obligation’), the administrative blocking of the film’s distribution was not an issue.

On the other hand, in a medium radically different from today, the characters originally may have been even less aware of the revelatory power of film; and even if the party functionaries were embarrassed by the presence of the camera, they may have thought – with justification – that if the crew had received permission to shoot the documentary from ‘higher up’, it could not be to their detriment, or if indeed it was, then the appropriate party officials would sort things out, as indeed the censors finally did by banning the film, thereby proving their vigilance. Thus, this film was made at one of those rare moments when the practitioners of power more or less openly undertook to present the motivations behind their decisions. It is in this capacity that The Resolution becomes a unique cinematic document revealing the workings of political decision-making, manipulation and assertion of interests.

Of course, there was a conscious editorial strategy behind the apparent ‘lack of means’ of the documentary film. The ‘passive’, observer camera engenders in the viewer the experience of being actually present; the cinematic tools of framing and editing appear to dissolve and become invisible. But one should never forget that what we see and hear of events is always the result of careful creative decisions, from the selection of events deemed worthy of preserving to the final edit. And in this regard, too, The Resolution is a remarkable work. Its dramaturgical structure evokes the arc of classical dramas, in which the calvary of the president of the cooperative whose removal turns into an archetypal story of the fall of the good. In this way the directors make a political statement solely by their recording of events. The local party functionaries come across as cynical and arrogant representatives of an authority that has complete disregard for the values of the community, whereas members of the cooperative standing by the president are the authentic guardians of democracy. This would have rated as an extremely strong political act even if the film had not been born in the midst of a dictatorship.

The two directors, Judit Ember and Gyula Gazdag, parted ways after The Resolution. However, despite being banned the film began to enjoy a second ‘secret’ life. In 1982, the Objektív Studio, one of the four big studios, carried out ‘technical restoration’ of the material originally made by the Balázs Béla Studio, and although the film continued to be officially banned from cinema distribution in Hungary, in 1984 it was screened as part of the Hungary Feature Film Festival. Judit Ember and Gyula Gazdag were awarded the director’s prize for their joint work by a professional jury. In parallel with this, the documentary went on to be shown abroad: it was presented in West Berlin, London, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In 1996, the International Documentary Association selected it as one of the 100 best documentaries of all time (the only Hungarian film to be thus honoured). While the effects of subjectivity and randomness can never be ruled out in such lists, the film’s values indisputably raise it up among the greatest. The persistent and systematic documentation of the quiet calvary of the cooperative president destined to fall captures on film the manipulative practice of power while the extraordinarily refined dramatic structure provides the experience not only of familiarity and understanding, but also compassion in the mind of the viewer.

Translated by James Stewart

Author Biography: Pál Czirják is a film historian and archivist at the Hungarian National Film Archive (NFI), Budapest.

This original essay was written for Working Together: The Cinema of Judit Ember, Liberating Cinema Film Series 2021.